|

|

| Funding for this site is provided by readers like you. | |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

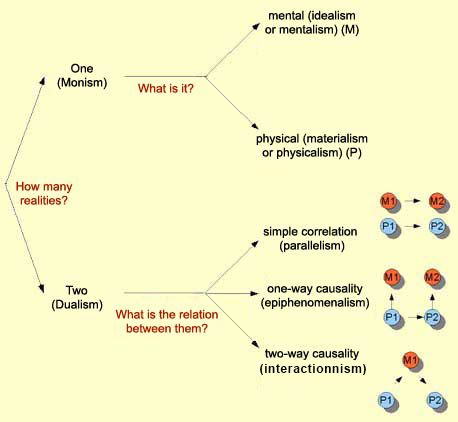

The idea of consciousness covers a variety of phenomena; the categories of consciousness as distinguished by philosopher Ned Block are described in the first box below. In 1994, at the first “Toward a Science of Consciousness” conference in Tucson, Arizona, philosopher David Chalmers proposed that the problems posed by the study of consciousness could be divided into two distinct types: the “easy problems” of consciousness and the “hard problem” of consciousness. When Chalmers talked about the “easy problems”, he was of course speaking in relative terms. These problems are “easy” in the same sense that the problems of curing cancer and sending a person to Mars are “easy”: they are far from having been solved, but scientists have a good idea of the steps that they must still complete to solve them.

The same classic methods can be used to investigate the mechanics of all of the unconscious processes (vision, memory, attention, emotions, etc.) that make consciousness possible. Thus, when it comes to the “easy problems” of consciousness, investigators can hope to identify the brain processes underlying them and attempt to understand why they have evolved. Or to paraphrase Chalmers, we can hope to find adequate functional explanations for these phenomena. The “hard problem” of consciousness arises from discoveries made in the field of physics in the first half of the 20th century. These discoveries made it hard to find a place in the world for consciousness. Everything was so much simpler before, when philosophers and scientists had no trouble in assuming that the reality of consciousness was at least as “real” as the reality of the physical world. But once the world in its entirety came to be understood as the relationships among forces, atoms, and molecules, that left very little room for the subjective aspect of consciousness. And it is precisely this aspect that constitutes the heart of what Chalmers calls the “hard problem” of consciousness, or what his fellow philosopher Joseph Levine calls the “explanatory gap”. For these two thinkers, no explanations about the causal role of our states of mind and their instantiation in a given nervous system (the easy problems) will ever tell us anything about the subjective dimension of consciousness or, to borrow the language of another philosopher, Thomas Nagel, about “what it is like” to be oneself and to experience qualia subjectively.

As often happens in new fields of study such as consciousness, a whole constellation of different solutions to the hard problem have been proposed, often contradicting one another. To help you understand them more clearly, the next main section of this page describes the various positions that various groups of philosophers have taken on the hard problem of consciousness, and how these positions are classified conceptually. This classification generally depends on whether the philosophers in question accept or reject certain premises, which often makes for some complex combinations of positions.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Collective Intelligence of Human Groups The Infinitely Large, Infinitely Small, and Infinitely Complex

|

Among all of the philosophical approaches proposed over the centuries to try to solve the “hard problem” of human consciousness, dualism and materialism are two that have gained the support of a considerable number of thinkers. But many of these thinkers have felt the need to nuance these two general theoretical positions so as to address the criticisms that have been levelled at them. For example, to avoid the pitfalls of substance dualism, some philosophers have proposed an approach called “property dualism”. Property dualism recognizes that everything consists of matter, but holds that matter can have two types of properties, physical and mental, and that the latter cannot be reduced to the former. Property dualism is also often referred to as “non-reductive physicalism”. According to this approach, pain, for example, would have a physical property (the action potentials transmitted by the C nerve fibres that sense pain) and, at the same, a conscious mental property (the feeling of pain).

For modern property dualists such as David Chalmers, this option does not constitute a rejection of science, but rather a call to broaden its horizons, by recognizing consciousness as a full-fledged entity, just as fundamental as space, time, or the force of gravity. But the question of how subjective states can influence matter without violating the laws of physics remains unresolved. Not to mention that property dualism leads to panpsychism—the idea that all matter (even a thermostat, even a rock) has some conscious properties, however limited they might be.

For epiphenomenalists, the impression that our intentions, desires, and feelings directly affect our behaviours is therefore only an illusion, an “epiphenomenon”. Thus we adults would be somewhat like a small child playing with a toy steering wheel attached to his booster seat while his parent drives the car. The child gets so wrapped up in his play that he ends up believing that he’s the one who’s actually driving. Similarly, we give ourselves the illusion that it is our minds that are actually guiding our behaviours. Nowadays, among those who accept the idea of a physical world in which conscious subjectivity exists, many are also prepared to accept that mental processes might not exert any causal influence on the physical world after all, even though common sense encourages us to think that our intentions, desires, and feelings do directly affect our behaviours. According to these thinkers, the subjective feeling of thirst that makes us head for the kitchen faucet has nothing to do with our taking this action. Even more surprisingly, if consciousness has no influence on our behaviour, then it follows that our behaviour would remain exactly the same even if we were zombies, that is, even if our brain activity were not accompanied by mental states. But it is hard to imagine ourselves as zombies, especially when you consider the verbal behaviours that we usually interpret as reflecting our mental states. David Chalmers has tried to show the difficulty of this position by caricaturing himself as a zombie with no mental states who is busy discussing consciousness with other zombie philosophers. Other philosophers, whom American philosopher

Paul Churchland has labelled “interactionist emergent property

dualists”, believe that mental phenomena, even though they

are not physical, can nevertheless play a causal role in the physical

world. Once the brain has generated the subjective sensation of

an odour or a colour, for example, this sensation could influence

the functioning of the brain in return. Once again, these emergent properties cannot be reduced to the basic properties from which they emerge. In other words, they can be neither predicted nor explained by the conditions underlying them. The classic example is the way that atoms combine to form a molecule with different properties. For instance, at room temperature, both hydrogen and oxygen are gases, but the water that forms from their combined atoms is a liquid. Some materialist neurobiologists regard this concept of emergence and its strange nature as an excuse for not buckling down to the task of actually studying the neural correlates of consciousness. Other materialists, however, invoke the concept of emergence when they offer neurobiological models of consciousness in which consciousness emerges from the complexity of the proposed neural processes. But, according to their critics, they thereby leave an “explanatory gap” that tends to reduce their position to a form of mysterianism.

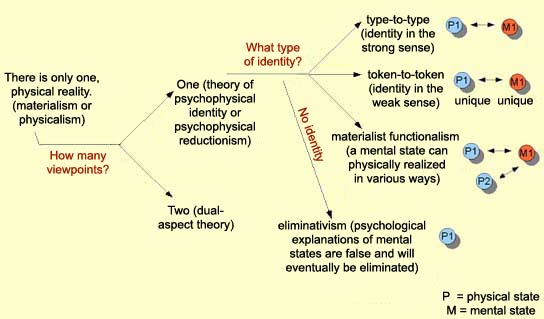

The materialist (or physicalist) alternative to dualism gets around this problem by positing that conscious states may not be distinct from physical states after all . The effect of our mental states on our behaviour is therefore no longer problematic, because both are part of the physical world. Some materialists opt for a “dual-aspect” theory that considers the brain and the mind to be the same thing, but seen from two different perspectives: one external and objective, the other internal and subjective. Other materialists, known as reductionist materialists, tend to simply reduce the mental to the physical. But they offer at least two different theories about the kind of identity relationship that exists between mental and physical events. Some reductionist materialists believe in type-to-type identity, in which a given type of mental event is considered identical to one, and only one, type of physical event. This is a theory of identity between two types of things—mental states on the one hand, and states of the brain on the other. For people who believe in type-to-type identity, if a flame burns your finger and makes you feel pain, this type of mental state is identical to the activation of a brain circuit that signals excessive, harmful heat. But many objections have been raised to the idea of type-to-type identity. For example, some people argue that before you can declare a given mental state identical to a given physical state of the brain, you would have to know precisely what types of mental states actually exist, so that you would not identify this particular mental state with a brain state that is actually identical to some other mental state. But there is nowhere near any unanimity as to what mental states actually exist. On the other hand, if we assume, for instance, that the love that a father feels for his children is identical to a certain state of his brain, it still seems far-fetched to claim that anyone who loves their children must have that exact same brain state. And what about other species? It does not seem impossible that in mice, for example, some types of pain may correspond to certain types of neurophysiological processes that are different from those found in the human brain. That is why the philosopher Ned Block has described the theory of type-to-type identity as “neuronal chauvinism”. In contrast, the other identity theory embraced by some reductionist materialists, token-to-token identity, holds that no two people can have the exact same mental state. Consequently, a given mental state is always unique to a given individual. This unique mental state will therefore be identified with a neurophysiological state that is equally unique to the brain of that individual. In short, a token-to-token identity is a specific, individual case of identity between a unique mental state and an equally unique brain state. Thus, whereas a “type” is a general concept, a “token” refers to a particular occurrence. In this version of identity theory, every individual can love his or her children in an entirely personal way, producing a mental state that is unique to that individual and identical to an equally unique neurophysiological state. But is it conceivable that two individuals could have exactly the same mental state at a specific point in time? If it is, as the critics of token-to-token identity believe, then there could be some cases where the same mental state is physically manifested in two different ways in the brains of these two individuals. How can we then still speak of identity when one thing can be identical to two different things? The answer to this question has come from another theory of the relationship between the body and the mind, known as functionalism. For functionalists, what is identical in the two different physical occurrences of the same mental state is the function—the complete set of cause-and-effect relationships between the internal mental states. Functionalism thus accepts the idea that mental states are internal and hidden, yet does not go so far as to identify them with qualia, which are purely subjective experiences. Nor does it adopt the behaviourist stance, from which the mind is regarded as a “black box” that should be set aside in order to focus on purely behavioural explanations. Also, functionalists, even though they believe that mental states are hidden, unobservable phenomena, nevertheless consider them part of the physical world. The classic functionalist analogy to describe this position is the analogy with a computer’s hardware and software. The hardware consists of the components that the computer is made of—integrated circuits, connectors, cables, and so on. The software consists of the various programs that the computer can run, such as your word processor or your e-mail package. These programs can often be installed on various types of hardware (PC, Mac, etc.), because the programmers have made sure to adapt the software’s essence—the causal structure of its components—to each of these types. What is essential is that when you type a command, it produces a certain internal state in the machine, and this state in return produces the right response on the screen. And that is exactly the way that functionalism envisions the human mind—in terms of causal relations among internal states. Consequently, just as various types of computers can run similar types of software, various types of brains could have similar conscious states if they have structural modules that perform the same functions. This is the “multiple realization” argument, that mental states can be realized in multiple ways, on various platforms, and hence not necessarily in a human brain. But functionalism does not necessarily require that the platform be physical, because there is no necessary logical connection between functionalism and materialism. The premise that there are mental states that are causally interrelated does not necessarily imply that these states are of a material nature. But given the current state of our knowledge, it seems rather implausible that there are causes and effects that are not physical. And in fact, the main defenders of functionalism are materialists. Contrary to behaviourism, functionalism accepts that human beings have mental states inside themselves and that these states are the source of their behaviours. But functionalism sheds no light at all on the “subjective“ side of our mental states, their “qualia”. Hence functionalists have trouble in responding to criticisms centered on the existence of qualia, such as Frank Jackson’s story of the neurobiologist who sees the colour red for the first time or Thomas Nagel’s discussion of “what it is like to be a bat”. Another objection to functionalism targets the hardware/software analogy, according to which the mind is to the brain as a software program is to a computer. American philosopher John Searle attacked this analogy with what some philosophers regard as the most difficult argument to refute: the “Chinese room” argument (see sidebar). Another problem that materialist functionalists create for themselves is that by denying the importance of the particular substrate of neural physiology, they distance themselves from the particular strength of materialism, which says that the only conscious states of which we know, those of human beings,come from the activity of their physical substrate, that is, the form and activity of their networks of neurons. Functionalism thus finds itself in the same position as epiphenomenalism, trying to explain how mental states can have an influence on the physical world. All of the positions discussed so far accept the existence of “mental states”, meaning desires, beliefs, intentions, etc., at the origin of our behaviours. But the “eliminative” version of materialism states that these popular concepts are quite simply false, even if they seem to have real explanatory power. The way that eliminative materialists see things, just as the setting of the Sun is an illusion that can be explained by the Earth’s rotation on its axis, so conscious mental states are only an illusion that will eventually be dispelled by progress in the neurosciences. That is why this form of materialism is called “eliminative”: it quite simply eliminates the concept that is causing the problem, i.e., mental states. For philosophers such as Paul and Patricia Churchland, two of the main proponents of eliminative materialism, no one is conscious in the phenomenal sense—the sense of the “hard problem” of consciousness formulated by Chalmers. Instead, all problems can be reduced to the “easy” problems that may eventually be solved without recourse to physical properties other than those that we already know. In short, philosophers like the Churchlands believe that psychological explanations of our mental states are only temporary stopgaps that will one day be replaced by new neurobiological models. Faced with arguments such as those of Jackson and his vision specialist who has never seen a colour, the eliminative materialists get around them by saying that one can speak of conscious states in two way: as being conscious, and as being physical. It is not a matter of two different properties, but rather of a single property that can be discussed in two different ways. It’s somewhat like discussing an actor’s role in a particular movie: you can talk about him using the name of the character he plays, or using his name in real life, but either way, you are talking about the same person, the same reality. Another example is temperature. You learn to think of it in degrees first, but then you learn that it is the average kinetic energy of the particles concerned—two ways of conceptualizing the same reality. Thus the eliminative materialists would say that Jackson’s vision specialist who is experiencing the colour red for the first time is basically just experiencing a new way of talking about the same reality.

|

|

|

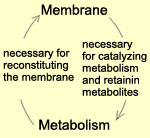

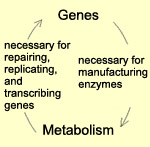

Shedding Some Light on the First Cell Membranes

|

|

Around the 1950s and 1960s, behaviourism, the paradigm that had dominated the experimental study of the human mind since the start of the 20th century, gradually gave way to the cognitive sciences, which developed two major theories of consciousness: cognitivism and connectionism. Cognitivism equates thinking with the manipulation of symbols and regards it as an algebra that operates on representations of the world, just as a digital computer does. Connectionism, in contrast, equates thinking with the operation of a network of neurons and argues that every cognitive operation is the result of countless interconnected units interacting among themselves, with no central control. Connectionism does, however, retain the idea of representation, which it defines as the correspondence between an emergent global state and some properties of the world. Some critics believe that this idea of representation smacks strongly of dualism and maintains a separation between the mind and the body, as well as between the self and the external world. This conception of the human mind has also been criticized as too passive, reducing it to an input/output device for processing information. Some authors, such as Ryle, Freeman, and Núñez, have even argued that the concept of internal representation was an error of category, or simply a fiction. These authors subscribe to a theory of human thought known as embodied cognition. They are influenced by pragmatists such as John Dewey and phenomenologists such as Merleau-Ponty, both of whom could conceive of actions and intentions without representations. The embodied-cognition critique of connectionism and cognitivism (and hence also of functionalism) revolves around the idea that the embodied experience of the individual in his or her environment plays a fundamental role in human thought. In addition to shedding new light on some of the astonishing cognitive abilities that we display every day (making unconscious inferences, coordinating speech and gestures, understanding language, etc.), the embodied cognition movement argues that many of the abilities that let us think about the world and interact with other people actually originated in the bodily experience of the individuals of our species. This way of defining cognition by intimately linking the body with thought has produced some interesting alternatives to the epistemological difficulties of the representational models (see first three sidebars), and in particular to the restrictions imposed by linear causality, the “subject/object” dichotomy, and “body/mind” dualism. Among other things, it allows for a rehabilitation of the role of the emotions in cognition, a reconsideration of our everyday unconscious thought mechanisms as probably being of capital importance in our cognitive apparatus, and a recognition of the evolutionary data showing that the human brain has evolved in large part to allow the organization of social life. Embodied cognition is also consistent with the work of thinkers such as Vygotsky who have emphasized the social and cultural environment as the main driver of human cognitive development. In the 1980s, a movement therefore developed that rejected the cognitivist and connectionist orthodoxy based on the idea of representation. To understand the essence of this new movement’s argument, consider the example of a baby who is learning to walk. No one teaches her any rules for doing so, as the cognitivist approach would postulate. Yet by trial and error, she learns how to maintain her balance on her articulated limbs, while avoiding obstacles that would upset that balance. The connectionist approach is probably more appropriate for describing what is happening in this case, but another approach would be to seek a more complete understanding of this phenomenon by considering this baby’s particular legs and the environment in which she needs to move about. This is the approach that was proposed by Francisco Varela, the author of many works that inspired the embodied cognition movement, notably The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience (1991). This movement does not deny all the contributions of cognitivism and connectionism, but does deem them insufficient. For example, it does not discard the idea of symbol manipulation, but sees it as a higher-level description of properties that in practical terms are embodied in an underlying distributed system—the network of neurons. For Varela, this network can therefore be used to describe cognition adequately, but for such a network to be able to produce meaning, it must necessarily have a history, and it must be able to act on its environment and be sensitive to variations in that environment. Indeed, in everyday life, what we observe in practical terms are embodied agents who are placed in situations where they can act and hence are completely immersed in their particular perspectives. For Varela, this is the subject on which cognitivism and the emergent properties of connectionism remain silent: our everyday human experience. This critique of the two major successive currents in the cognitive sciences places Varela in an epistemological position known as the theory of autopoiesis (see sidebar). This theory is accompanied by a particular methodology rooted in Buddhism (see box below). Together they form what is conventionally called the paradigm of enaction.

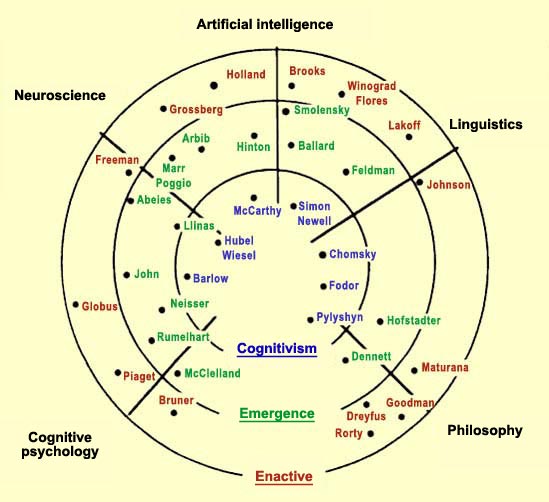

Conceptual chart of the state of the cognitive sciences in 1991, with the contributing disciplines and the various approaches (the term “Emergentism” here is equivalent to connectionism). Source: The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience, by Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991.

From the perspective of enaction, perception has nothing to do with a static, contemplative attitude. Instead it consists in a form of action that is guided perceptually, in the way that the perceiving subject manages to guide his actions in his local situation of the moment. From this perspective, the surrounding world is shaped by the organism just as much as the organism is shaped by the surrounding world. In the language of enaction, the senses of smell and vision thus become not mere sensory receptors, but ways of enacting meanings. Thus the reference point is no longer a world predetermined independently of the perceiving subject, but rather the subject’s own sensorimotor structure. Consequently, categorization emerges from our structural coupling with the environment (see sidebar), and our conceptual understanding of the world is necessarily shaped by our experience. Cognition therefore is not representation, but intrinsically depends on the capabilities of our own bodies. Enaction also invites researchers in the cognitive sciences to place the greatest stock in first-person accounts and the irreducibility of experience, while refusing even the smallest concessions to dualism. This is also why enaction claims a kinship with phenomenology, not in its transcendental or highly theoretical sense, but rather in its etymological sense, meaning that which is manifested in the “first person”, in embodied thought. This thought must be “mindful and aware”, and hence non-abstract, and open to the body that makes it possible. This practice of mindfulness/awareness, Varela tells us, can be found in the Buddhist tradition. That is why he takes an interest in certain Buddhist practices calling for the gradual development of the ability to be present in both the mind and the body, both in meditation and in the experiences of ordinary life (see box below). The main idea of enaction is that the cognitive faculties develop when a body interacts in real time with an environment that is just as real. This idea has had repercussions in several fields of research, in particular situated robotics (see box below). Enaction also stimulates debates in still broader fields, such as consciousness, the nature of the self, and the very foundations of the world. Because if it is in the very nature of a cognitive system to function in and thanks to an embodied subjectivity, then the body, far from being cumbersome excess baggage, becomes both the limitation on all cognition and the condition that makes all cognition possible. And the body/brain system, far from being a mere cognitive machine that provides itself with representations of the world and finds solutions to problems, instead contributes to the joint evolution of the world and of the individual’s way of thinking about that world. In addition, that way of thinking is conditioned by the history of the various actions that this body has performed in this world. To paraphrase the 19th century French philosopher Jules Lequier, it is a process of doing, and by so doing, of creating oneself. This concept of the psyche is also in line with Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget’s research on child development, which tended to show that the child’s psyche is constructed through its contacts with the environment, which leads the child to become conscious of itself and of the outside world simultaneously. Both for Piaget and for Varela, the outside world is no longer the framework for our experience, against which the “I” stands out as a distinct entity. In other words, the relationship between the I and the world is no longer one of differentiation, but rather one of reciprocal engendering. The world, though it seems to have been there before thought commenced, actually is not separate from us: it is our body that enables us to discover a part of it. It is produced by the history of a structural coupling between a body and an environment, a coupling that is different for every living system. This co-determination between cognitive system and environment thus calls into question the entire representational aspect of cognitivism and connectionism, which implies a world that is pre-formed and gradually represented. From the enactive perspective, it is instead the historical sequence of actions in context that causes the emergence of a world of meanings—an “enacted world”, to use Varela’s expression.

|

|

The idea that we are fully conscious of the world around us has been discredited by a multitude of experimental data. These data indicate that our environment is far too rich and complex for our nervous systems to process all of the information from it continuously in real time. Whereas the classical model of consciousness proposes that we are conscious of the entire world around us, in reality we pay attention to only a tiny proportion of our environment, while ignoring the rest. Because of our limited cognitive abilities, evolution appears to have favoured the emergence of two complementary types of mental processes: attentional processes and unconscious processes. The phenomena of consciousness, attentional processes, and unconscious processes have all arisen from the same need: to facilitate effective action in a complex environment. First, let us consider the attentional processes that are so intimately connected with consciousness. We know that attentional processes existed far back in the evolutionary past, because they have been detected even in flies. Some scientists even believe that consciousness itself may be nothing more than an extension of the attention mechanism associated with working memory. Michael Posner and Mary Rothbart, for example, find it reasonable to hypothesize that phylogenetically speaking, our conscious functions developed from the attention mechanism. Indeed, it seems quite plausible to say that when some ancient predator first noticed a prey animal, then focused all of its attention on it, that predator had just taken its first step toward conscious thought. And that first step was most likely followed by a second, in which the predator engaged in some rudimentary reasoning involving various internal and external stimuli and then either triggered or inhibited a movement to capture the prey. One thing is certain: there are many theories about attention, but all of them say that we are attentive to something when we select it. Attention occurs when we focus on a certain stimulus by being more sensitive to it than we are to others. Our attention may thus be spatial, or based on a property of an object, or a type of object, etc. For example, suppose you are watching TV, and you are also vaguely aware of the sound of a conversation in the next room, the noise of a fan, and the smell of bread in the toaster. But then suppose the toast gets stuck in the toaster and starts to burn. You will unconsciously attribute a meaning of danger to that smell, then shift your attention to it abruptly. The corollary to this selective aspect of attention is that when you pay attention to one thing, you automatically ignore a lot of others. Our human attention resources are limited, and it is hard for us to allocate them to more than one object at a time. If you try to pay attention to two complex tasks simultaneously—for example, driving in rush hour while negotiating a contract over your cell phone—you will necessarily neglect one or the other, very likely with negative consequences in either case. If you ever read the written transcript of a conversation, evidence of this same phenomenon will leap off the page: you’ll be surprised at the number of pauses and “ums”, because when you’re involved in a conversation yourself, you simply ignore these things. The same process explains why it’s so hard to find errors in a text that you’ve written yourself: your attention is so focused on what you’re trying to convey that you overlook minor misspellings. Thus, the only stimuli that reach our consciousness are those that we have selected as worthy of attention. If anyone is still skeptical that this is the case, a phenomenon such as inattentional blindness (see box below) will generally manage to convince them. Attention also comes into play when a task or a stimulus requires special processing. In such cases, attentional processes may be required in order to hold certain data in memory, to discriminate between two similar stimuli, to anticipate certain events, to plan a course of action, or to co-ordinate various behavioural responses so as to achieve an objective. Attentional processes are therefore more specific than wakefulness or awareness. Wakefulness and awareness are preconditions for attention and depend on more general processes arising from the activation of diffuse neural systems in the brainstem, such as the norepinephrine system in the locus coeruleus. Neuroscientists also frequently distinguish two different kinds of attention mechanisms. The first is initiated from the bottom up, that is, by neuronal signals from specialized processing modules whose job is to detect and process stimuli. These signals then trigger a global activation of the neural control networks. The archetypical bottom-up attention behaviour is the orientation reaction: sensory organs such as the eyes or the ears detect a new stimulus in the environment, and the entire body then turns toward this stimulus to learn more about it. This reaction explains why it is so hard to look away from the TV screens in sports bars or airport waiting areas: the changing images on the screen are constantly drawing your attention. When the initial stimulus is visual, our bottom-up attention responses depend on a network of interconnected areas of the brain that include the parietal lobe, the pulvinar and the superior colliculus. The second kind of attention mechanism operates from the top down, such as when the neural control networks execute an action that is motivated by a goal. Our thoughts, motivations, perceptions, and emotions then become available to consciousness when we pay attention to them.

This ability for attention to be an active phenomenon has also been well demonstrated in experiments where the subjects were required to press a button as soon as a visual target lit up. These experiments showed that the subjects’ reaction time was faster when they were shown an indication of where the target was going to light up shortly before it did so. And when they were shown an intentionally misleading indication, their response time was slower than when they were given no indication at all. These results clearly show that our expectations influence our perceptions, or, in other words, that attention can be a mental process directed from the top down. In short, we live in a complex environment where stimuli from all directions make claims on our attention, but our attention focuses only on those stimuli that are new or already have some meaning for us. We may think that we are conscious of the entire scene around us, but that is indeed an illusion, as phenomena like change blindness clearly demonstrate. It is therefore a trap to accept the standard, naïve, realist view of the world around us as a place where “objective reality” is composed of objects whose characteristics are independent of our senses. The projective nature of perception means that the content of our consciousness—each individual’s psychic reality—is greatly influenced both by biological predispositions and by learning, both of which are projections of the distant or recent past onto the present.

We therefore cannot speak of consciousness and attentional processes without also considering the extensive unconscious activity that is going on in our brains at all times. On the one hand, attention plays a fundamental role in learning by amplifying the important representations that enable us to take appropriate actions at any given time. But on the other hand, by thus increasing the quality of certain mental contents, learning increases the likelihood that a given piece of mental content will be at the centre of the attentional processes of our subjective consciousness sometime in future. That is why many people believe that the true relationship between the self and the world is one of reciprocal engendering. Many experimental findings support this description of consciousness in terms of quality of representation (see sidebar concerning Munakata’s experiment). From this standpoint, the quality of representations is therefore a continuous variable, a continuum that allows a gradual transition from the unconscious to the conscious. This quality gradient between unconscious and conscious, which is shaped by learning, also suggests that the corresponding representations depend on the same underlying processes, rather than on two distinct neural systems. But although learning, by increasing the quality of a stimulus, can facilitate its access to consciousness, recurrent consciousness of a stimulus can paradoxically return it to the realm of the unconscious, through habit or automaticity. We can therefore describe consciousness (or the realm of the explicit) as a peak between two domains of lesser consciousness in which the two extremes would be two very different types of unconscious.

This transfer from the conscious to the unconscious clearly comes into play in the learning of motor skills, such as how to ride a bicycle, or ice skate, or tie your shoelaces. In the beginning, everything is conscious and laborious, but as you practice, it all becomes automatic and unconscious. In a process of automatization such as this, our conscious experience is diminished as we gain in expertise. But the opposite can also happen, when we try to master the fine distinctions that characterize a particular field of knowledge, such as oenology or philosophy. In this case we are no longer engaged in procedural learning, but rather in explicitly expanding our knowledge in a particular field. And the more we learn about the complexity of this field, the more conscious we become of new distinctions that make it even more rewarding. We can therefore distinguish three different possible situations involving two different characteristics of knowledge: its availability to our consciousness and our ability to control our conscious representation of it. When both availability and controllability are low, this knowledge is implicit (unconscious). When both availability and controllability are high, this knowledge is explicit (conscious). And when availability to consciousness remains high but controllability drops back to a very low level (as the result of habit or automaticity), then the knowledge is said to be automatic.

|

|

As a result, attempts have been made to develop new models that incorporate these data on the brain’s anatomy and function and integrate them into a coherent whole that explains the various aspects of our conscious processes. The following paragraphs briefly describe some of these neurobiological theories of consciousness. Many of these theories have some concepts in common, which the most optimistic of their authors believe points to the beginnings of an overall explanation of how the brain goes about “producing” consciousness. |

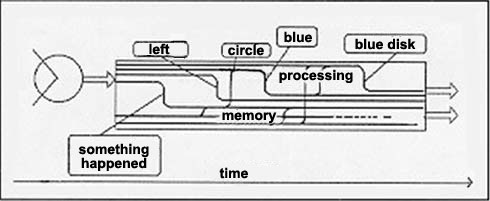

| Daniel Dennett is a philosopher, but probably one of the philosophers who are trying the hardest to integrate the findings of neuroscience into their conception of consciousness. Dennett wants to put an end to what he calls Cartesian materialism, a position that rejects Cartesian dualism but accepts the idea of a central (though material) theatre from which consciousness springs. To escape from this Cartesian materialism, Dennett proposes two metaphors that he considers more consistent with the neuroscientific data: “multiple drafts” and the “virtual machine”. For Dennett, there is no little homunculus inside the human brain, no little “self” sitting in front of the theatre of consciousness and observing or even directing the spectacle before it. In his multiple drafts model, consciousness is not a unitary process, but a distributed one. At any given time, several concurrent neuronal assemblies are activated in parallel and competing with one another to be the centre of attention—to be “famous”, as Dennett puts it. The conscious self is therefore nothing more than “fame in the brain”, fragile and changing like any other ongoing reconstruction. Thus, the result of this competition is not an “average” of the various drafts, but rather the success of the one that is the most effective in and best adapted to a given situation. What Dennett is positing here is a process of selection similar to what Edelman has called “neural Darwinism” (follow the Tool module link). According to Dennett’s multiple-drafts model, a given piece of conscious content arises from a rapid succession of events in the brain whose order in time cannot be determined. Various neuronal assemblies distributed throughout the brain respond to the various properties of an object (during an interval of about one-fifth of a second). Consequently, the answer to the question “When did I become conscious of such-and-such an event?” can only be vague, never precise. The following diagram attempts to illustrate this point.

According to Dennett’s model, with these multiple drafts in constant competition, the single, conscious narrative flow so familiar to all of us and depicted in the Steinberg cartoon above can only be an illusion, just like the Cartesian theatre. To explain this illusion, Dennett posits the existence of a virtual machine that runs in serial fashion on a “hardware platform” that operates in massively parallel fashion—i.e., the human brain. This virtual machine would be a sort of mental operating system (like Linux or MS-DOS), capable of transforming the inner cacophony of the brain’s parallel activity into a conscious, serial narrative flow. It is this virtual machine that would enable us to think about our own thoughts and engage in deliberations with ourselves. Unlike the behaviourists, Dennett thus does not dismiss what each of us may subjectively report about our emotions, feelings, or mental states. But he does not grant these reports any special status either. He regards them as real data, but as data concerning the way that people feel things, and not about how these things actually are (see sidebar on heterophenomenology). For Dennett, the task clearly becomes to understand how this illusion is generated.

|

| The theories that invoke the concept of a global workspace date back to the work done by Alan Newell and Herbert Simon in the cognitive sciences in the 1960s and 1970s. Newell and his colleagues were the first to show the usefulness of a global workspace in a complex system composed of specialized circuits. By providing a place to pool the information that each of these circuits had processed, this workspace would allow problems to be solve that no one of them could have solved on its own. That in short is the great principle of the global workspace, which scientists have continued to apply and enhance ever since. In fact, most neurobiological models of consciousness incorporate some aspects of the global workspace concept. Examples include Gerald Edelman’s “global cartography”, Rodolfo Llinas’s mechanism of global synchronization from the thalamus, Antonio Damasio’s cortical convergence zones, Daniel Schacter’s “conscious attention system”, Francisco Varela’s “brainweb”, and the model of Jean-Pierre Changeux and Stanislas Dehaene, who make the neuronal workspace their primary hypothesis. But ever since the 1980s, it is Bernard Baars who has been the strongest proponent of this model, which attempts to answer the famous question: how can a phenomenon such as consciousness, in which everything happens in series, with only one conscious object at a time, emerge from a nervous system that basically consists of countless specialized circuits that operate in parallel and unconsciously? Baars’s answer: by having a workspace where the information processed by these specialized circuits is made accessible to the entire population of neurons in the brain.

Baars thus suggests that there is a close connection between global availability of information on the one hand and consciousness on the other. In his view, this global accessibility of information, made possible by a global workspace, is precisely what we subjectively experience as a conscious state. The “easy problems” and the “hard problem” of consciousness are thus here regarded as two different sides of the same coin. The global workspace is a process that involves first convergence and then divergence of information. Baars thinks that this process can best be understood through the metaphor of a theatre stage where attention acts as a spotlight cast on certain actors. These actors represent the content of consciousness selected by competition among specialized circuits. What we have here is a Darwinian selection process by which certain actors (pieces of conscious content) become “famous” for a fleeting moment. During that moment, this conscious information is disseminated or made accessible to the vast audience of unconscious circuits that fills the theatre. Baars argues that this way of formulating the theatre metaphor does not make it what Dennett calls the “Cartesian theatre” and criticizes so harshly. Indeed, the Cartesian theatre has always been predicated on the existence of a single point, such as the pineal gland identified by Descartes himself, where everything is brought together within a “self” that receives the conscious thought or perception—almost as if there were only one spectator in the audience watching the entire stage. In contrast, in Baars’s theatre metaphor, a multitude of entities, all of which remain unconscious, have access to a particular piece of information at the same time. Baars thereby not only avoids the problem of regression to infinity, but also offers a straightforward definition of consciousness as this in-depth exchange of information among brain functions, each of which is otherwise independent of the others and unaware of what they are doing. The

idea that consciousness has an integrating function makes it easier to understand

several of the human brain’s capabilities, including working

memory, learning

(both

explicit episodic and implicit), voluntary

motor control, selective attention, and

so on. Baars reminds his readers that the purpose of these details of the theatre metaphor is not to “explain” consciousness, but to provide tools that can be used to organize the existing data, to clarify certain concepts, and to formulate testable hypotheses, in particular the involvement of certain structures in the brain, so as to better understand this complex phenomenon. |

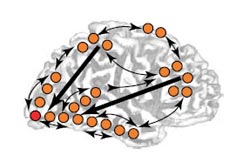

| Some authors agree that talking about a conscious workspace probably represents some progress over the idea of consciousness that prevailed in the mid-20th century. But others think that this idea is some like the earlier notion of the “dormitive virtue” of opium, which provided no information at all about the underlying mechanisms by which opiates affect the brain. What then does this global workspace consist of, in concrete terms? If it is a set of neural pathways that interconnect the various parallel processors in the brain, then which pathways are they? And what determines whether the activation of any given set of neurons will be propagated into the global workspace? Many neurobiologists, including Jean-Pierre Changeux and Stanislas Dehaene, are conducting research programs to attempt to answer these questions. Changeux and Dehaene start from the premise that the brain does in fact contain a conscious global workspace that combines all of the information quietly processed in the background by the numerous independent, unconscious modules to which it is connected. Noting that layers II and III of the prefrontal, parieto-temporal, and cingulate cortexes contain pyramidal neurons with long axons that could reciprocally interconnect distinct cortical areas, Changeux and Dehaene identify these circuits as possibly constituting the neuronal substrate of this global workspace. These circuits become activated only during conscious processing and are very strongly inhibited in individuals who are in a vegetative state, or under general anaesthesia, or in a coma. Both of these facts lend support to Changeux and Dehaene’s hypothesis. In contrast, the brain’s unconscious processors are more localized, generally in the sensory cortical areas. In 2006, Changeux and Dehaene’s research using brain-imaging techniques led them to distinguish three major forms of mental processing in the human brain: subliminal, preconscious, and conscious. For conscious processing to occur, there are two conditions that that must be met: a sufficient level of alertness (being awake rather than asleep, for example) and sufficient bottom-up activation, in other words, a response must be occurring in the primary and secondary sensory areas. But these conditions do not suffice to let a stimulus enter consciousness. For example, some individuals may be awake and display an activation of the extrastriate visual areas of the cortex, yet deny having seen any stimulus whatever. Hence, according to Changeux and Dehaene, for a piece of information to access consciousness, a third condition also must be met: the activation of the associative cortexes by these neurons with long axons that create a reverberation between distant neuronal assemblies. But why do certain pieces of information become conscious while others do not? To explain this phenomenon, Changeux and Dehaene distinguish four situations. In the first situation, the information remains unconscious, because it is processed by circuits that are not anatomically connected to the conscious neuronal workspace (for instance, the circuits that regulate the body’s digestive functions). But in the three other cases, the access door to the conscious workspace does exist.

But in both of these last two cases, the transition from preconscious to conscious is abrupt, as is the case for any non-linear, self-amplified dynamic system (see sidebar). This transition is also always accompanied by an activation in the parieto-frontal and anterior cingulate cortex. When this activation reaches several richly interconnected associative areas, two things can happen. The activation can undergo a reverberation in the workspace and thus remain available for a much longer time than the initial stimulus lasts. The activation can also rapidly propagate into several specialized systems of the brain that can then make use of it. In contrast to the classic binary distinction between not conscious and conscious, this model divides the non-conscious state into subliminal and preconscious ones, thus providing a classification into three distinct states (or four, if you count vegetative regulatory processes, which by definition are always unconscious). This distinction makes sense, in light not only of the results of brain-imaging experiments, but also of phenomena such as inattentional blindness, which show that even when there is substantial preconscious activation, a stimulus can remain unconscious if the individual is not paying attention to it. |

| To the various levels of accessibility of the contents of consciousness described by Changeux and Dehaene, another continuum must be added: that of the brain’s ability to form its own representation of the “self”. How does this representation of self contribute to conscious experience? This question has been central to the concerns of researchers such as Edelman, Tononi, Llinás, and, especially, Antonio Damasio. In his book Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain, published in 1994, Damasio argues that conscious thought depends substantially on the visceral perception that we have of our bodies. Our conscious decisions arise from abstract reasoning processes, but Damasio shows that these processes are rooted in our bodily perceptions, and that it is this constant monitoring of the communications between the body and the brain that lets us make informed decisions. This is what Damasio means by his concept of “somatic markers”, which also clarifies the role and the nature of the emotions from an evolutionary standpoint. The somatic manifestations of the emotions are processed in working memory so as to “mark” perceptual information from the external environment with an affective value and thus assess the importance of this information to the organism. This process is essential for any decisionmaking that involves the survival of the organism in question. In a later book, The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness (1999), Damasio develops his model further to account for the various possible levels of consciousness of self. The visceral monitoring described above becomes the proto-self, which is a moment-to-moment perception of the body’s internal emotional state and is made possible by the insula, among other structures in the brain.

Damasio also distinguishes extended consciousness from what is referred to by the general term “intelligence”. According to Damasio, extended consciousness provides access to the widest possible body of knowledge, whereas intelligence is related more to the ability to manipulate this knowledge in order to devise new behavioural responses. Damasio also regards this uniquely human extended consciousness as the source of such faculties as creativity, systematic consideration of others, and moral consciousness .

|

This idea that there are various degrees of consciousness and that the emotions constitute a fundamental elementary form of it is defended by many scientists, including neuropharmacologist Susan Greenfield. Greenfield stresses that the activity of the neuronal assemblies distributed in the various parts of the brain is constantly modulated by the neuromodulatory neurons associated with an individual’s emotional state. There are also some molecules, in particular some peptides, that may influence not only the forming of assemblies of neurons in the brain, but also the body’s hormonal and immune system. The feedback loops between the brain and the body are therefore due not only to the vegetative nervous system, but also to all of these chemical molecules that can act on the brain and the body simultaneously. From this perspective, consciousness, whose most primary levels appear to be related to the emotions, is not simply a matter of brain activity, but rather an experience involving the body as a whole. This description comes closer to the conception of the human mind advanced by Freeman and Varela, who attribute a central role to the individual’s body situated in its environment. These authors thus take exception to the traditional cognitivist approach, in which the human brain is regarded as a system that applies rules to manipulate internal representations of the world. |

| We will now briefly discuss neurophysiologist Walter J. Freeman’s approach to the problem of consciousness. But to do so, we must first go back down to the cellular (neuronal) level, because Freeman focuses less on the anatomy of brain structures than on the way that neurons communicate with one another and the patterns of activity to which this communication gives rise in the brain as a whole. Freeman observed that the neuronal connectivity of the human brain engenders chaotic activity that, like weather phenomena, follows the laws of non-linear dynamics (or “deterministic chaos”—see sidebar). He therefore applied the mathematical tools of non-linear dynamics to interpret the electrical states observed in the brain. By analyzing the electroencephalograms (EEGs) of human brains while they were performing many tasks, Freeman showed that the various rhythms of the human brain do it fact follow the “laws” of spatial/temporal chaos. Behind what seems to be nothing but noise, these chaotic fluctuations actually display regularities and properties consistent with those of human thought. One example is the capacity for rapid, extensive changes. Another is the brain’s ability to almost instantly transform sensory inputs into conscious perceptions. Vast assemblies of neurons can change their activity pattern abruptly and simultaneously in response to a stimulus that may be very weak. This destabilization of a primary sensory cortex travels to other areas of the brain, where it is “digested” in a way that is specific to each individual, depending on the content of that particular individual’s memory. This is why, according to Freeman, far from being harmful, the chaotic activity of millions of neurons is what makes all perception and all new thoughts possible. This is also why Freeman thinks that phenomena such as consciousness cannot be understood solely by examining the properties of individual neurons. Just as a hurricane that develops from the collisions of billions of air molecules affects the physical environment, so an overall pattern that emerges from the activity of billions of neurons throughout the cortex affects, for example, the motor areas of the brain so as to produce a given set of body movements. In the latter case, the loop is then closed when the environmental changes caused by these movements in return produce a perception that transforms the brain’s general activity once again. Freeman

therefore does not regard perception and action as two independent phenomena,

one input, the other output. Instead, he sees them as the

same process enabling the individual to act upon the world. Thus he goes further

than the idea of perception as an active phenomenon that is currently accepted

today. This model offers a way out of the impasse of trying to determine the origin of conscious will through linear causal reasoning: instead it proposes a process of circular causality—an epistemological breakthrough made possible by the mathematics of chaos. The origin of a conscious action therefore should be sought not solely in the brain of the individual who takes that action, but also in that individual’s continuing relationship with other individuals and with the rest of the world. Because according to Freeman, what we call our decisions are constructed in real time by the behaviour of our entire bodies, and we are informed of these decisions on the conscious level only after a slight delay. Thus consciousness would intervene only to smooth out the various aspects of an individual’s behaviours, to modulate them, and probably to legitimize them in relation to the entire set of meanings that constitute that individual’s personality. In the terminology of

dynamics, consciousness would correspond here to an “operator”, because

it modulates the brain dynamics from which past actions have arisen. This conception

is consistent with a hypothesis proposed by William James in 1878, that consciousness

interacts with the brain’s processes and is neither an epiphenomenon

nor a first cause.

|

| The dynamic approach just described in terms of Walter J. Freeman’s work actually is part of a broader theoretical approach called “embodied cognition”. Contrary to the computational approach, the dynamic approach deals with neuronal activities rather than with symbols, and with global states of the brain observed by means of functional brain imaging, rather than with calculations and rules. Embodied cognition theory, of which Francisco Varela was one of the greatest proponents, challenges the separation between human cognition and its embodiment. For Varela, and for the many researchers who have come to embrace this approach, we cannot understand cognition, and hence consciousness, if we abstract it from the organism embedded in a particular environment with a particular configuration. In these “ecologically situated” conditions, in which “situated cognition” occurs, any perception results in an action, and any action results in a perception, as we have just seen with Freeman. Hence a perception-action loop constitutes the foundational logic of the neuronal system. Cognition, consciousness—in short, the individual’s entire inner world—emerges from that individual’s actions; it is an “enacted” world . Cognition is continuously enhanced by movement, because the human brain has been constructed in this way throughout the history of phylogenesis. Non-linear mathematics have also contributed greatly to our understanding of the phenomena of self-organization and emergence that are inherent in the embodied approach, through the concept of an “attractor”, borrowed from the theory of dynamic systems. Current knowledge thus irretrievably distances us from the traditional, causal model of consciousness as a simple matter of input, process, and output, patterned on the operation of computers. Instead, the ideas of circular causality, and the primacy of action, the emotions, and a living body in a given environment provide us with a richer matrix in which to attempt to understand human consciousness.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|