|

|

The

Various Speeds at Which We Perceive Time

One of chronobiology’s

important contributions has been to demonstrate that the

human body reacts differently to medications according to

the time of day when they are administered. This idea was

scarcely recognized in the early 1980s. Now it has become

the foundation of an entire discipline, known as chronopharmacology.

By taking the human body’s

internal circadian rhythms into account, health care professionals

can recommend a time of day when taking a given medication

will optimize its benefits or, in some cases, reduce its

side effects and/or toxicity. For example, some medications

that act on certain hormones have no effect at all if taken

at 6:00 PM but are fully effective if taken at 7:00 AM.

|

One noteworthy characteristic

of the human biological clock is that it is independent of

ambient temperature —one of the rare systems in the

human body that is not slowed down when the ambient temperature

is cold or sped up when it is hot. This ability of the body’s molecular

clockwork to compensate for temperature is

essential, because it must maintain its circadian rhythm

in both summer and winter. |

|

|

The behaviour of almost all land animals, including humans, follows

rhythms that are of endogenous origin but that are also modulated

by the daily variations in light and darkness. These cyclical fluctuations

in behaviour are known as circadian

rhythms.

Circadian rhythms are biochemical, physiological, and behavioural

cycles whose period is approximately 24 hours. These cycles are

co-ordinated by molecular

oscillators in the neurons of the suprachiasmatic

nucleus. These oscillators represent the key component in the

human biological clock, which is synchronized with the alternation

of day and night by specialized

light-sensitive cells in the retina.

The reason that the human biological clock needs to be continuously

adjusted to the level of the ambient light is that its endogenous

cycle does not last exactly 24 hours. The actual length of this

period has been studied in numerous

experiments with complete temporal isolation, in which the

subjects were deprived of any light or auditory cues that might

indicate the time of day. The values that these studies have found

for the period of the natural human circadian cycle ranged from

24.2 to 25.5 hours. Thus the Latin roots of the word “circadian”—circa,

meaning “around” and dies, meaning “a

day”—are quite apt.

It is this light-entrained adjustment

mechanism that lets the body’s central clock track the alternation

of day and night precisely. This central clock in turn co-ordinates

the activity of many

other biological clocks that are located in various peripheral

tissues and that have their own molecular oscillators. This

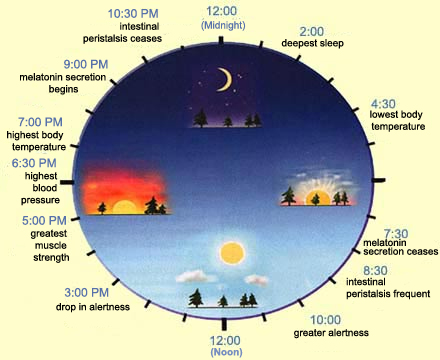

is why most of the body’s major physiological functions fluctuate

with the time of day. Examples include body temperature, hormone

secretion, urine production, blood circulation, metabolism, and

even the growth of hair!

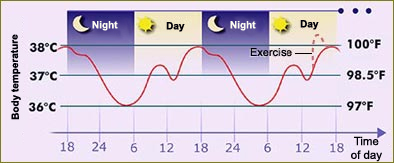

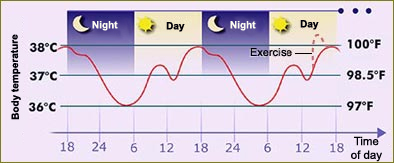

These fluctuations usually go through a peak

and a trough that coincide with particular times of day. For example,

human body temperature is always lowest at night.

Adapted from: Gerry

Wyder

Of course, body temperature can also fluctuate

under exogenous influences such as physical activity levels, stress

levels, the presence of infection, or simply the ambient temperature.

But in experiments where subjects lie awake but still for 30 hours

or more, endogenous variations in their body temperature are also

observed. In addition to the major drop in body temperature at

night, there is also a slight decline from early to mid-afternoon.

This latter temperature drop, far more than having a full stomach

after lunch, would appear to explain the reduced alertness and

sleepiness that many of us experience at this time of day.

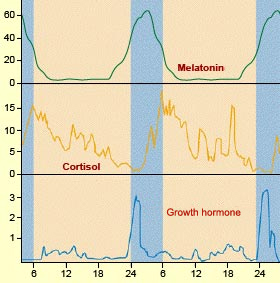

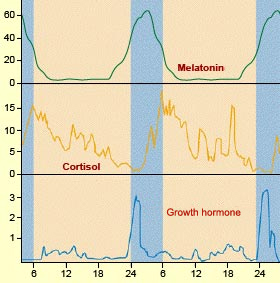

Other physiological parameters also undergo substantial

endogenous fluctuations over the course of the day. The

secretion of several different hormones is one example.

During the daytime, the levels of melatonin, a

hormone manufactured in the pineal

gland, are almost undetectable in

the blood. The pineal gland starts to secrete melatonin

in mid-evening, as darkness falls, and its secretion peaks

between 2:00 and 4:00 in the morning. |

|

In the case of the hormone cortisol,

peak secretion occurs just before a person wakes up, so that this

hormone’s level is highest when the person gets out of bed,

thus contributing to the general activation of the body.

The secretion of human

growth hormone, which is essential for bone and muscle growth in

children, takes place mainly during deep

sleep, which occurs mostly at

the start of the night. In adults, this hormone plays an important role in

metabolism, promoting the synthesis of proteins, helping to burn fats, strengthening

bones, and so on.

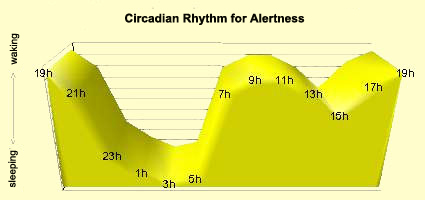

Wakefulness and sleepiness

are the two aspects of a single fluctuating state whose circadian

cycle is divided into two sub-cycles of about 12 hours each.

In other words, people who are placed in an

environment devoid of time cues will display a bidaily

rhythm of propensity to sleep.

The first and longest period of sleepiness occurs

around the time that you are used to going to bed and is deepest

between 3:00 AM and 6:00 AM. This is the time of day when

your metabolism and body temperature are at their lowest. So

is your alertness; if you are awake, you are physically clumsier,

and your mind feels sluggish.

The second daily period of sleepiness occurs

12 hours later, between 2:00 PM and 4:00 PM.

This period is shorter than the one that occurs

at night, but we all know it well—it’s

the mid-afternoon slump. Contrary to popular

belief, it has nothing to do with the heat of

the afternoon or with digesting the noontime

meal. Studies have shown that people who live

in the warm temperatures at the Equator experience

two troughs in their wakefulness/sleepiness cycle

just as North Americans do, and that people feel

sleepy in the afternoon even if they haven’t

eaten any lunch. (Moreover, most people don’t

experience this same kind of sleepiness after

breakfast or dinner.)

Thus, the fluctuations in our wakefulness

do in fact depend on our internal biological clocks. And

a short nap in

the afternoon would appear to be beneficial for most people. |

|

|