|

|

| Funding for this site is provided by readers like you. | |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

Infinitely Large, Infinitely Small, and Infinitely Complex

|

|

What is consciousness? One way to try to define this so familiar yet so mysterious phenomenon is to try to state what it is not. In other words, when is someone no longer conscious? In one sense, it could be simply when they close their eyes and thus lose their conscious visual experience. In another sense, it could be when the dentist gives them an anaesthetic before pulling a tooth, so that they lose their consciousness of pain. Consciousness is also what we lose when we fall asleep. But here things get more complicated right away, because we are conscious of our dreams. Despite their lack of coherence and their sometimes fantastic features, dreams often feel like intense conscious experiences. So we might say that is only when we reach the stages of deep sleep that we truly lose consciousness. And even then, it would be more accurate to say that we have very little consciousness, rather than none at all—for example, a mother may still hear her child crying even when she is in deep sleep. Many characteristics of what we call consciousness are also gradually lost by people suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. They become detached from everything going on around them and are no longer even sure of their own identity. And there is something even more disturbing about seeing someone in a coma after a traumatic brain injury, because there is a body, obviously alive, yet displaying no manifestations of consciousness.

Another problem is that we use the word “consciousness”with many different meanings. This constitutes a sizable obstacle to the study of consciousness, though some of the differences are mainly differences of degree rather than of kind. Nevertheless, when we talk about consciousness without specifying which of its many manifestations we are referring to, we are courting confusion. Here are some of the meanings that we give to the word “consciousness”:

And as if all these senses of the word were not enough, we also talk about “raising the consciousness”of our fellow citizens, with regard to political issues, for example. In this instance, the reference is to what is generally called moral consciousness. It develops during childhood, but also whenever the focus of our attention shifts from ourselves to other people, or to our species as a whole, or to the entire planet. Scientific knowledge about consciousness in these various senses is also very uneven. For example, scientists know a great deal about several brain structures that control consciousness in the sense of wakefulness. But when it comes to understanding consciousness in the sense of a particular subjective experience, there are still some tremendous problems to be solved. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Christof Koch, a Romantic Reductionist

|

The subjective nature of human consciousness has long intrigued and fascinated the world’s great thinkers. Long before scientists began to talk about the “hard problem of consciousness”, many philosophers had tried to explain how subjective consciousness fits into the objective world. This inquiry has given rise to many different philosophical traditions, each with its own conception of the relationship between the mind and the body, grounded in the particular broader vision of reality that each of these traditions embraced. Telling the story of each of these traditions would take too much time here, so instead we will simply summarize four of them that have had their proponents throughout recorded time: idealism, dualism, materialism, and mysterianism. Idealism holds that nothing exists in the world except our conscious experiences. Idealists therefore regard the material world as a mere illusion of our consciousness.

Dualism is the philosophical tradition embraced by those who wish to reject neither the existence of the material world nor the existence of the mind. Dualists believe that there are two worlds: one of mind, and one of matter. But dualists must then explain how a life of the mind is possible in a body of flesh. Which raises a question that poses great difficulties for dualists: the possible interaction between these two realities. René Descartes believed that the exchanges between the material body and the immaterial soul took place through the pineal gland. Descartes had noticed that this brain structure appeared to be the only one that did not come in a bilateral pair, but instead was single and centrally positioned. With our modern scientific knowledge of the importance of the pineal gland for the human biological clock, what Descartes proposed may seem somewhat far-fetched, but at the time he lived, it was an honest solution to a crucial question that remains the Achilles heel of dualist philosophies to this day.

Mysterianism, for its part, argues that there probably is no solution to the problem of subjective consciousness and that it will always remain a mystery to us. People who adopt this stance believe that our sense of uneasiness in dealing with the hard problem of consciousness may be due to the limited cognitive capacities of our brains. Hence, the reason that we can’t imagine how neural activity can produce subjective feelings would be the same as the reason that we can’t hold 100 numbers in our working memory or visualize 7-dimensional space: the cognitive limits of the tool with which we think. Each of the preceding four positions has

been the target of criticism, and in response their champions

have refined each of them, giving rise to numerous

variants, especially in the case of dualism and materialism. |

|

Around the middle of the 20th century, a number of major figures in fields such as psychology, computer science, linguistics, anthropology, mathematics, and neurobiology held a series of conferences in New York City, with an ambitious goal: to pool their knowledge to create a new interdisciplinary science that could explain the many facets of the human mind. What emerged from these meetings are now called the cognitive sciences, and their stated purpose is to combine the data from numerous disciplines so as better to understand such diverse phenomena as perception, language, reasoning, and consciousness. Before discussing the major currents that have emerged in the cognitive sciences, let us briefly review the historical context in which they emerged. As we have just seen, the question of how the human mind functions and what relationship it has to the brain and the rest of the body has preoccupied thinkers for many years, and many philosophical approaches to this question have been proposed over the centuries. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, there was a school of psychology known as structuralism, represented by such figures as Wilhelm Wundt and Edward B. Titchener. The structuralists used introspection to attempt to describe the elementary components of the human mind. For example, according to the structuralists, a sensory perception was based on the structure of the associations between numerous sensations (whence the name “structuralism”). The structuralists believed that by describing the possible combinations of these elements, they could deduce laws as general and powerful as those governing the physical world. The structuralist approach was criticized not only because of its implicit dualism, but also because of the difficulty of experimentally testing the introspection on which it was based. In response, another school of thought emerged that was radically opposed to structuralism. This school was known as behaviourism. According to its pioneers, such as John B. Watson and B. F. Skinner, no scientific approach to psychology could be built on subjective states, which are essentially private. In contrast, their new psychology would be based not on personal judgments about feelings and states of mind, but solely on the experimental study of behaviour.

With unobservable mental processes thus excluded from the field of scientific psychology, notions such as consciousness and the concepts associated with it became devoid of interest. The behaviourists did, nevertheless, make many useful discoveries, in particular concerning the operant conditioning of behaviour, in experiments with rats and pigeons. Obviously, this school of psychology was extremely focused on the influence of our environment on our mental processes. Watson even went so far as to state that the human mind is shaped entirely by the rewards and punishments that its receives from the environment, and not by any genetic influences. To caricature this radical behaviourist position, its detractors would joke that one behaviourist who met another in the street would have no choice of greeting except “You’re fine today. How am I?” During this same period when the behaviourists were active—the mid-20th century—the series of conferences mentioned at the start of this section gave rise to a new school of thought known as cybernetics (follow the Tool module link to the left). Cybernetics looks at the way that information circulates both in living organisms and in complex artificial systems designed by human beings. Hence it is no surprise that computer science, in its infancy at the time, drew much inspiration from cybernetics. At the same time, linguistics was also developing into a genuine scientific discipline, dedicated to one of the most sophisticated human mental abilities: language. In the 1960s, critiques of behaviourism by linguists such as Noam Chomsky revealed its shortcomings when it came to studying complex phenomena such as human language. These attacks dealt just as harsh a blow to behaviourism as the writings of Watson had to structuralism earlier in the century. In short, as all of these new disciplines

(cybernetics, computer science, linguistics, etc.) evolved, the

human mind came to be treated less and less as a black box, and

the disciplines themselves began to interact in creative ways

that some called the cognitive

revolution. |

|

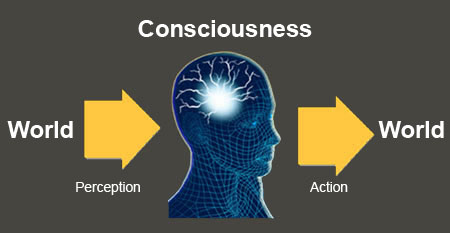

As noted above, people use the word “consciousness” to mean many different things. But one image that it brings to mind for many of us is that little “me” sitting comfortably inside our heads, watching what’s going on in the world as if it were a movie. From time to time, your inner me may even comment on this movie, in the “small inner voice” that we all know so well, or appear to freely decide on a course of action or behaviour on the basis of what it sees in this movie. In this popular view, consciousness is seen as a container for ideas and images, with a window onto the world for purposes both of perceiving it and of taking action in it. Some call this the “naïve realist” model of consciousness; it is the model that appeals to our common sense, the model that we typically have by default.

The Classical Model of Consciousness

Philosopher Daniel Dennett takes vigorous exception to this model (see sidebar). He nicknames it the “Cartesian theatre”, because it assumes that we examine ideas “in the light of reason”, which illuminates them like a spotlight illuminates a theatre stage or a projector illuminates a movie screen.

A list of the characteristics of this model of consciousness would look something like this:

As neuroscientists acquired more and more data about the workings of the brain, this model came in for more and more criticism, in particular because it makes so little allowance for all of the behaviours that we carry out unconsciously. Nowadays, in fact, the counter-reaction has reached the point that journals on consciousness are filled with reports on experiments demonstrating the presence of unconscious processes in the brain . But why so much insistence on the search for unconscious processes? In the history of science, many important breakthroughs have come when something that was previously assumed to be a constant (for example, gravity, or atmospheric pressure) was ultimately proved to be a variable (see sidebar). The classical model presents consciousness as a unitary, indivisible, “all or nothing” phenomenon—in short, a constant. But is it really? With the classical model of consciousness, as with any other model, the scientific method is to try to invalidate it, to see, for example, whether it can be proven incorrect in certain respects, such as whether unconscious processes exist, or whether a mental representation can become conscious gradually, rather than all at once. This is why so many neurobiologists are

trying to demonstrate the existence of unconscious mental processes

in perception, thought, and action, and they are succeeding in

doing so. Because the classical model of consciousness leaves

no room for unconscious processes, every successful scientific

demonstration of their existence demonstrates a flaw in this

model. And these

flaws are so numerous that this model is on the verge of

collapsing. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A

Monthly Podcast On Cognitive Science Christof Koch, a Romantic Reductionist

|

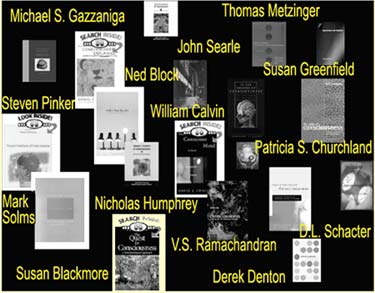

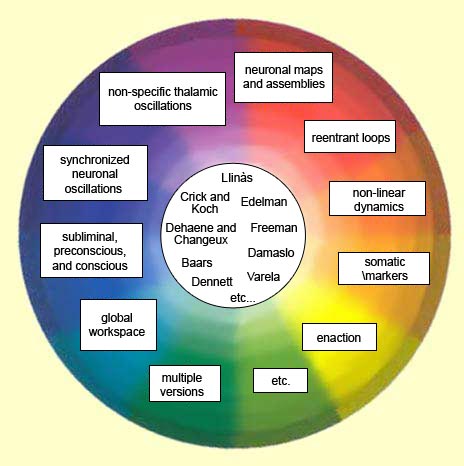

But the 1990s saw an explosion of scientific enthusiasm for such initiatives, in large part because of research in the neurosciences and the accessibility of increasingly high-performance devices for imaging the brain (follow the Tool Module link to the left). As a result, attitudes about studying the neurobiological bases of consciousness have changed dramatically. As the American philosopher John Searle put it when describing the value of the Journal of Consciousness Studies: “We don’t know how it works and we need to try all kinds of different ideas.” This ferment of new ideas has given rise to many neurobiological theories of consciousness that often have some key concepts in common. The figure below attempts to illustrate these commonalities. At the centre of the circle are the names of some important authors of such theories, while around the outside are some key concepts that are shared (with minor variations) by the two authors or sets of authors whose names appear adjacent to them.

Many people see this conceptual convergence as a sign that a “mature” theory of consciousness is starting to emerge. One thing is certain: concepts from the neurosciences are now enabling us to go beyond the classical model of consciousness and avoid its flaws and shortcomings. Even so, the subjective essence of “what it means” to be conscious remains an issue that is very difficult to address scientifically. Some scientists ascribe genuine importance to this subjective aspect of consciousness, but add that if consciousness is to be investigated effectively, better methods of interpreting the relevant subjective data will have to be found. Other scientists attempt to minimize the importance of the subjective nature of human consciousness. Francis Crick, for example, believes that only once we have managed to understand the neurobiological mechanisms of consciousness will we be in a position to understand its subjective qualia, and that until then we therefore should not accord them too much importance. This is a common strategy in science: concentrate on the things that are more amenable to experimentation, while hoping that those which are less so will subsequently become clearer in light of the experimental results obtained. One of the forerunners of this neurobiological approach to the study of consciousness was the French neurobiologist Jean-Pierre Changeux, who defended a neuronal theory of thought in his book L’Homme neuronal, first published in 1983 and now available in English under the title Neuronal Man: The Biology of Mind. Changeux clearly posits a causal relationship between the structure of the brain and the function of thought. From this relationship, it follows that consciousness is the result of interactions among neurons in which the nerve impulse takes a path that could ideally be described objectively. And this path, it must be remembered, is not fixed, but instead alters itself with use, thus constantly modifying our representations of the world. The similarities that the main neurobiological theories of consciousness share with regard to certain concepts are also seen in the neuronal circuits and brain structures that these theories identify as playing a key role in conscious thought. Obviously, not all parts of the brain participate equally in conscious processes. There are, for example, numerous unconscious processes that take place beneath the cortex and have no conscious counterpart. It is therefore important to stress that the cognitive neurosciences do not attempt to analyze the functioning of these structures in isolation, but rather to understand the orderly functioning of the brain as a whole, at the most integrated level possible—that is, at the level where ion channels, receptors, synapses, neurons, and neuronal assemblies all come into play collectively and simultaneously. When philosophers impatiently point out that the models of consciousness proposed by the neurobiologists are still unclear, the neurobiologists freely admit that they are only in the early stages of a long struggle to penetrate the mysteries of consciousness. They also point out that in scientific research, investigators must begin by looking for correlations between observations before they start inferring any causal mechanisms (see sidebar). When this search for the “neural correlates of consciousness” is thus viewed as part of a long-term effort, many of the criticisms levelled at it become irrelevant. Christof Koch is a good example of a neurobiologist who applies this gradualist approach, conducting experiments on the most elementary forms of attention. He hopes that once we understand them, the problems that now seem unsolvable will become much simpler. Like many other neurobiologists, Koch acknowledges that we may have to discover some new laws governing the physical world before we can explain consciousness, and that it may even remain a mystery forever. But the scientists of the future will have to make that judgment, which he says they can do only after all empirical avenues of inquiry have been exhausted (if such a thing is possible). And it is not only neurobiologists who take exception to the view of David Chalmers that consciousness is such a hard problem that it is beyond the reach of neuroscience to solve. Some philosophers too, of whom the most representative are probably Paul and Patricia Churchland, find it counterproductive to treat human consciousness as a special case, distinct from all the other problems involved in understanding the human mind. For the Churchlands, and for other philosophers and researchers who are identified as eliminative materialists, all questions about consciousness can be reduced to what Chalmers calls the “easy problems” and eventually be solved. Simply put, the concepts of popular psychology that we use to explain our mental states (intentions, beliefs, desires, etc.) are only approximations that will eventually be replaced by neurobiological models that have yet to be developed. And according to Patricia Churchland, the fact that it is currently very hard for us to imagine a solution to the problem of consciousness tells us absolutely nothing about whether or not this phenomenon can actually be explained. In her view, it is too easy to conclude that a phenomenon such as consciousness is inexplicable simply because current human psychology cannot grasp it.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|