| |

| |

|

The Sense of Self |  |

| | |

|

|

|

One should avoid jumping to conclusions

about the correlations that exist between a few properties of consciousness and

the sometimes rather peculiar properties of the world of the infinitely small.

Molecular and quantum theories of consciousness are often criticized for this

tendency to try to turn such correlations into overall explanatory models of consciousness.

For example, the correlation between the administration of certain anaesthetics

and loss of consciousness might be used to justify a model that assigns a central

role to the proteins

of the microtubules that are affected by these substances. Or the unpredictable,

changing nature of consciousness might be linked to the principle

of uncertainty and the superimpositions of states in quantum physics. Even

if a new molecular mechanism were in fact found to be essential for consciousness,

there would still be little chance that this mechanism alone explained the entire

complex phenomenon of human consciousness. Instead, this mechanism would have

to be integrated into a theory that provided explanations at higher levels of

organization (cellular, neurological, psychological, etc.) as well. An excellent

analogy is the way that the molecular mechanisms involved in the body's immune

defences must be combined with environmental

and psychological factors to explain these defences completely. |

| |

| CAN QUANTUM EFFECTS EXPLAIN CONSCIOUSNESS? | |

Most of the hypotheses

that try to draw connections between subjective consciousness and physical events

in the brain do so at the cellular level: that of individual neurons or neuronal

assemblies. This approach—the search for the

“neural correlates of consciousness”—is based on the assumption

that the key to conscious processes can be found in the activities of these nerve

cells. And in fact, the activities of the neurons and their communications with

one another are central to many models of consciousness, such as those involving

thalamocortical

loops, synchronous

40 Hz oscillations, or the influence

of the intralaminar thalamic nuclei on neuronal synchronization. But

there are also many theories that attempt to relate the functioning of human consciousness

to structures at the molecular level, and even to the very strange effects of

the quantum

physics of the infinitely small. As scientific methods for investigating the

infinitely small become more refined, more and more mechanisms will likely be

discovered below the neuronal level, and it will be no surprise if some of these

new mechanisms are indeed found to have an effect on human consciousness. One

molecule that may well play a role in the mechanisms of consciousness is the NMDA

receptor. This large protein molecule takes the form of a channel passing

through the neuronal membrane and serves as the binding site for glutamate, an

excitatory neurotransmitter

released into the synapses

of a great many neurons. Once released into the synaptic gap, glutamate binds

to the postsynaptic neuron’s NMDA receptor, causing this channel to open

and thus initiating a

whole series of biochemical reactions that make this synapse more efficient.

NMDA receptors thus act as critical components in

the mechanism by which neurons form lasting associations by strengthening their

connections with one another, thus creating what are known as neuronal

assemblies. These assemblies occupy a prominent place in many neurobiological

models of consciousness, so it seems entirely reasonable to assign the NMDA

receptor molecule a significant role in the conscious processes of the human brain.

And that is precisely what German neurobiologist

Hans Flohr has done. Flohr suggests that those synapses that have NMDA

receptors are the ones that are most readily strengthened when an organism detects

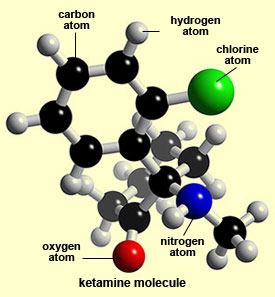

regularities in its environment. Flohr also points out that anaesthetics

such as ketamine block the normal excitatory effect of glutamate on NMDA

receptors and cause loss of consciousness. | |

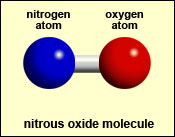

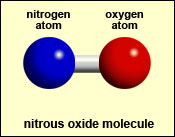

| Another

anaesthetic, nitrous

oxide (“laughing gas”) is a completely different type of molecule

from ketamine. The nitrous oxide molecule acts elsewhere in the series of reactions

induced by the NMDA receptors but ultimately produces similar effects. |

Flohr therefore concludes that normal functioning

of the NMDA receptors and their secondary

messengers is necessary for consciousness. But

many objections have been raised to Flohr’s approach, which does not involve

any quantum effects as such. Some of his critics have pointed out that besides

the NMDA receptor, there are countless other molecular mechanisms that must work

properly if normal conscious function is to be maintained. Others critics have

observed that normal functioning of the NMDA synapses is also important for unconscious

processes and for the forming of neuronal assemblies that are not involved

in thought processes.

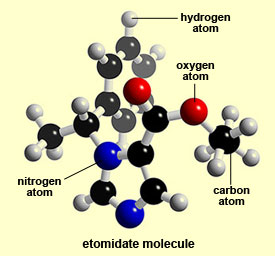

| Another major objection to Flohr’s hypothesis

is that some other anaesthetics operate rather differently from ketamine and nitrous

oxide. Etomidate, for example, puts subjects to sleep by potentiating their

GABA

receptors. According to Flohr’s hypothesis, etomidate would have to

inhibit the NMDA receptors indirectly, but we have no evidence that it does. And

even if it did, the two drugs should have the same anaesthetizing effects. But

that is not the case either: etomidate does not have the same analgesic effects

as ketamine. | |

This raises an even broader problem. There

are countless substances that can render us unconscious, and they do so in such

different ways that the resulting state of unconsciousness must be regarded as

something more than the mere lack of something called “consciousness”.

Hence, though scientists can generally attempt to understand phenomena by observing

the effects of their absence, when the phenomenon in question is consciousness,

this approach is quite insufficient. |

|