|

|

| Funding for this site is provided by readers like you. | |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

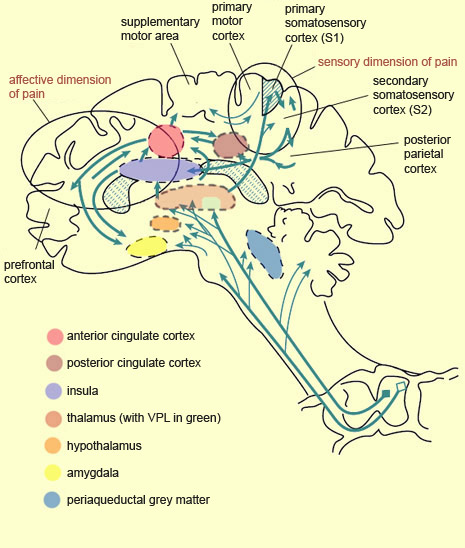

The existence of so many different ascending pathways for pain suggests that they do not all depend on a single system terminating in a “pain centre” somewhere in the brain. On the contrary, the perception of pain is controlled by a number of different brain structures, which confirms the multi-faceted nature of this phenomenon. Once a pain message has passed through the reticular formation in the brainstem and on to certain nuclei in the thalamus, it reaches the cerebral cortex. The primary somatosensory cortex (S1) receives the axons of the neurons of the ventral posterolateral nucleus (VPL) of the thalamus, while the secondary somatosensory cortex (S2) receives pain messages both from S1 and from the thalamic nuclei. Neuroscientists generally assign S2 a role in recognizing pain and remembering past pain, while associating S1 with discriminating the various properties of pain. The preservation of somatotopic organization all the way up to the S1 cortex is what lets the brain determine the location of pain in the body, while the activity level of the neurons in S1 corresponds to the intensity of the pain stimulus. For example, if you place your hand under a running hot-water tap, the hotter the water gets, the more nerve impulses the neurons in your S1 cortex will generate. Brain-imaging studies have shown that the higher the neural activity level in S1, the more intense the pain, as evaluated subjectively by the individual concerned. In other studies, hypnosis was used to suggest to the subjects that a pain stimulus was less intense than it actually was. Brain images then showed that under these conditions, the activity level in the S1 cortex decreased. Remarkably, however, when a stimulus of the same intensity was applied to all of the subjects, but some were given the hypnotic suggestion that it would be very painful and others that it would not, the activity level in the S1 cortex remained constant among all the subjects. However, in the anterior cingulate cortex, whose activity level is associated with the affective component of pain, this level varied with the nature of the suggestion, thus confirming that these two areas play distinct roles in the perception of pain.

The explanation for this association between the negative affect of pain and the activity of the anterior cingulate cortex is that this structure incorporates sensory inputs, including pain stimuli, into cognitive processing, so as to allow the production of appropriate motor responses, such as avoidance behaviours. Because emotions give rise to motivations which in turn give rise to actions, one can readily understand the importance of the anterior cingulate cortex in affective reactions to pain that require an immediate behavioural response. Though the anterior portion of the cingulate cortex is the one most often discussed in the pain literature, research by German neuroscientist Burkhart Bromm has shown that the posterior cingulate cortex responds to nociceptive messages first (about 220 milliseconds after the nociceptive stimulus is applied). This activity then moves on to the medial and anterior portions of the cingulate cortex, before subsiding in the frontal cortex about 300 milliseconds after the stimulus began. Scientists also believe that the posterior cingulate cortex may merge the negative affect of pain, along with its location, nature, and intensity, into a single unified perception, through its connections to the parietal cortex,which plays a recognized role in integrating various sensory modalities. The posterior portion of the parietal cortex is also involved in attention to painful stimuli. So is the dorsolateral region of the right prefrontal cortex, another part of this attentional network in the cortex. Researchers are well aware that diverting attention from a painful stimulus can substantially diminish the subjective sensation of pain, and that this subjective sense of comfort is accompanied by an objective decrease in activity in the parts of the brain that are associated with pain. The prefrontal cortex is involved not only in the “higher” functions, which often involve attention, but also in learning nociceptive sensations and hence in developing negative affect associated with them. Hence the prefrontal cortex is extremely well placed to play a role both in anticipating and controlling pain. For example, in experiments where subjects’ brain activity was monitored while they were anticipating and actually receiving painful electric shocks, two conditions were used. In one, a cream was applied to the place on the subjects’ bodies where they were going to receive the shock, and they were told that this cream was an analgesic, whereas actually, it was only a placebo. In the other condition, no placebo was used. When the shock was administered to the subjects who had received the placebo, they reported less pain and showed less neural activity in some brain areas associated with pain, such as the thalamus, the primary and secondary somatosensory cortexes, the anterior cingulate cortex, and the insular cortex (also known simply as the insula). In contrast, while these same subjects were anticipating the shock (and, presumably, the pain relief associated with the placebo), they showed greater electrochemical activity in their prefrontal cortex and in an area of the midbrain that includes the periaqueductal grey matter. Because the prefrontal cortex is also associated with certain forms of working memory—in other words, with temporarily storing ideas, information, and thoughts so that they can be processed cognitively—one can readily see how this function might enable it to play a role in the anticipation of pain relief that is the source of the placebo effect. As for the periaqueductal grey matter, its activation in parallel with the prefrontal cortex during the anticipation of relief from pain tends to support an earlier hypothesis that prefrontal mechanisms trigger the release of endogenous opioids in the periaqueductal grey matter when the placebo effect is experienced. In addition, this nucleus in the midbrain receives information from numerous other brain structures associated with the integration of emotional processes. The periaqueductal grey matter and the area around it also receive inputs from the ascending nociceptive fibres; these inputs too can trigger the descending control mechanisms that this area applies to the neurons of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Neuroscientists now know that this endogenous analgesia can be triggered by the stimulation of several other subcortical structures, running from the medulla oblongata to the diencephalon. These structures include the raphe nucleus (which, along with the periaqueductal grey matter, has one of the most powerful analgesic effects), as well as the lateral reticular nucleus, the nucleus of the solitary tract, the locus coeruleus, the parabrachial area, and the lateral hypothalamus. Other subcortical structures also contribute to various pain-related phenomena. For instance, the transmission of nociceptive information from the reticular formation and the non-specific thalamus to the hypothalamus—perhaps the most important autonomic regulatory structure in the brain—increases the secretion of stress hormones and the activation of the sympathetic nervous system. The same projections, by activating the striatum, also encourage the largely automatic motor alarm responses triggered by pain stimuli. The significant interconnections between the anterior cingulate cortex and the amygdala, a key site for affective visceral regulation, account for the sweating, accelerated heart rate, elevated blood pressure, and nausea caused by intense pain. Lastly, the insula’s particular anatomical location, and its close connections with the limbic system, make it an ideal candidate to serve as an interface between sensory information from a person’s body and that person’s particular cognitive state at any given moment. And a subjective sensation such as pain is constituted precisely through the combination of this sensory and cognitive information. The insula, and more especially the right anterior insula, is one of the brain structures most commonly activated not only directly by a pain stimulus, but also when people look at pictures of painful situations and imagine themselves experiencing them. Indeed, research on the neuronal

substrates of empathy shows that there is a partial overlap between the areas

of the brain that are active when an individual is experiencing pain and those

that are active when he or she sees someone else in pain, and that the overlapping

areas include the anterior cingulate cortex and the insula. In contrast, however,

looking at an image that evokes fear

(another negative emotion associated with pain) causes increased activity in the

anterior cingulate cortex and in structures such as the amygdala, but not in the

insula. Thus, though both fear and pain cause unpleasant emotional states associated

with reactions of withdrawal and protection, their neurological substrates overlap

only partially. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|