|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 2004, U.S. neuroscientist A.

Vania Apkarian used magnetic resonance imaging to compare the brains of healthy

persons with those of people suffering from chronic back pain. In the latter group,

he observed a thinning

of the grey matter in the brain comparable to the loss of grey matter

observed in 10 to 20 years of aging. And the longer these people had been living

with this chronic pain, the greater the volume of grey matter they had lost.

This loss was especially evident in the thalamus and the prefrontal cortex, an

area associated with problem-solving. This finding was consistent with Apkarian’s

earlier observation that people with chronic pain took longer to solve certain

mental-skill-testing problems than healthy people did. Scientists are well

aware of the

harmful effects of stress on certain neurons in the brain that are particularly

involved in memory. But it is still hard to say whether this stress is directly

responsible for the thinning of the grey matter, or whether the stress is instead

the source of chronic pain, which then in turn causes the reduction in brain volume.

|

Studies have shown that the nucleus

accumbens, a key part of the brain’s reward

circuit, is activated during certain experiments that employ nociceptive stimuli.

Moreover, in many cases this activation appears to be associated with a variation

in the level of endorphins

in the vicinity of the nucleus accumbens. The fact that dopamine

is also involved in the analgesia produced by the placebo

effect is consistent with this finding, because the neurons of the nucleus

accumbens are highly sensitive to this neurotransmitter, which they receive from

the ventral

tegmental area. These findings tend to support the hypothesis that

there are specific physiological mechanisms behind what we subjectively perceive

as a continuum, from the onset of pain to its subsidence and

then on to pleasant and highly pleasant sensations. This same idea that pain

and pleasure are part of a single spectrum can be found in the writings

of philosophers from past centuries, such as Spinoza

and Bentham.

| | |

The

scientific search for a single “pain centre” in the brain has proven

fruitless. If such a centre existed, then millions of people might be relieved

of their chronic

pain by treatments to remove this centre surgically or neutralize it chemically.

But no such centre has been found. Pain is a subjective phenomenon with multiple

dimensions, some discriminative, some affective, and others cognitive, so it is

no surprise that science has shown that any given sensation of pain is actually

produced by the interactions of a network

of brain structures that are activated by a particular nociceptive stimulus.

Science has also shown that the activity of this network

is highly sensitive to “top-down”

regulatory processes, which would explain phenomena such as the placebo

effect. The way we experience a given source of pain is also influenced by

our personal experience and our cultural

heritage, which means that an even broader range of brain structures are involved.

That said, neuroscientists do now acknowledge that there is at least a partial

degree of functional specialization among the brain structures involved in the

various components of pain. Researchers are now attempting to associate different

subsets of brain structures with these different components of pain and thereby

propose an overall working model of pain. Given the complexity of the phenomenon

that these models are supposed to represent, they are still the subject of much

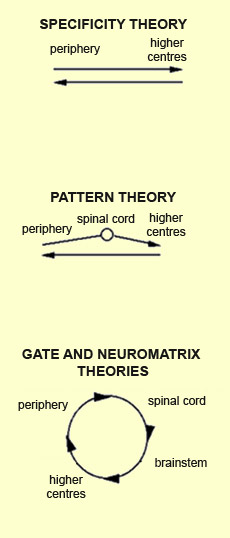

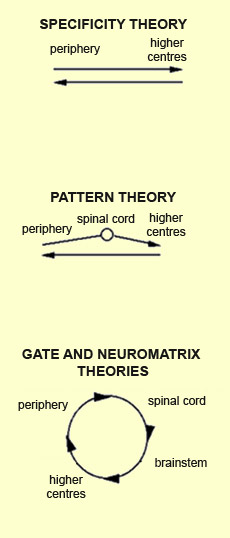

lively debate. Broadly speaking, the underlying concept

of theories of pain has evolved over time from one of linear causality to one

of circular causality. In the early theory of intensity, pain

was deemed to result from the excess activity of certain nerves that were not

necessarily pain-specific. Then, in the 17th century, René

Descartes was one of the first authors to discuss pain as a specific sense,

just like the senses of sight,

hearing, and smell. In 1894, Von Frey stated an explicit

theory of the specificity of sensations. According to this theory,

the type of nerve ending determines the nature and quality of the sensation perceived.

The resulting information then travels basically from the periphery to the higher

centres, where it reaches something like a “pain centre”, then travels

back downward as motor control information, without having been altered in any

significant way. Thus this theory does not allow for any possible changes of psychological

origin, such as might result from attention

or from past experiences that give a particular meaning to a particular situation.

In this model, the brain and the subcortical relays are nothing more than passive

receptors.

Source: Charest, Lavignolle, Chenard, Provencher and

Marchand, “École interactionnelle du dos”, Rhumatologie,

46, 221-237, (1994)

| | Unable

to provide suitable explanations for phenomena such as chronic pain, specificity

theory subsequently gave way to various pattern theories of pain.

These theories added to the linear ascending pathway various relays that begin

the process of integrating the activity of nerve fibres that have different receptive

properties. Such integration would take place, for example, in the gelatinous

substance of the spinal cord, the ventral posterior nuclei of the thalamus,

and the somatosensory cortex. Motor control signals would then be returned downward

in linear fashion. The development of the gate

theory of pain starting in the 1960s, and of neuromatrix

theory after that, was based on the finding that pain results from a

multitude of interactions and information exchanges at several levels in the nervous

system. The ascending nociceptive information is modulated at each of these multiple

relays before it is integrated into a perception of pain. Perhaps the chief advantage

of this circular model of pain is that it provides a better explanation of how

the nociceptive, discriminative, affective, and behavioural components of pain

can all influence one another. | The

concept of the neuromatrix of pain was first advanced by Canadian psychologist

Ronald Melzack, in the late 1980s, in an attempt to explain the strange but very

common phenomenon of “phantom

limb” pain, in which people who have had a limb amputated feel very

real pain that seems to be coming from that limb. This phenomenon clearly shows

that pain is not generated by a one-way system. Melzack’s proposed explanation

was that pain is actually generated by neural activity in a network composed of

several different structures in the brain, and that this network can generate

pain even when there is no sensory stimulus to trigger it.

In the case of phantom-limb pain, Melzack proposed, the conflict between the visual

feedback that the limb is absent and proprioceptive representations that it is

present might cause confusion in the neuromatrix, and this confusion would then

generate the pain. Evidence in support of this hypothesis has been provided by

experiments in which mirrors were used to give amputees with phantom-limb pain

the visual illusion that their amputated limbs were still present. In some cases,

this measure was effective in relieving the phantom-limb pain.

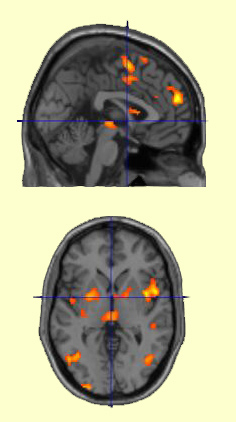

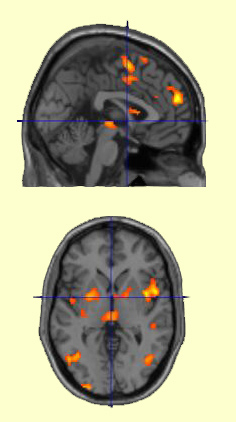

Activation

of structures of the pain neuromatrix, including the insula, the anterior cingulate

cortex, the periaqueductal grey matter, the medial prefrontal cortex, and the

supplementary motor area | | This

neuromatrix, or pain matrix, thus consists of all the parts of the brain whose

activity fluctuates when an individual is experiencing pain—a vast neural

space in which various,

distinctive types of pain can be encoded. Each of these types of pain has

what Melzack calls its own special neurosignature: a unique activation

pattern of the neuromatrix or of some subset of it. (Other scientists use the

term neuronal

assembly to describe this kind of association of neurons.) And because the

details of the connections in the brain of each individual are different, each

individual’s neurosignatures are necessarily different too. Likewise, because

synaptic connections can be modified by experience, any given neurosignature

in a given individual’s brain will change structurally with the passage

of time. | To account for all the

different facets of the phenomenon of phantom pain in amputees, Melzack proposed

a neuromatrix comprising numerous

brain structures involved variously in the discriminatory, affective, cognitive,

and motor aspects of this experience. Melzack’s proposed neuromatrix included

at least three major neural circuits whose importance has been confirmed by the

numerous brain-imaging studies that followed. The first is a lateral spinothalamic

ascending nociceptive pathway, which performs a discriminative function

and includes the ventral posterior nuclei of the thalamus and the somatosensory

cortex. The second is a medial spinothalamic pathway, which has a more affective

and motivational function and involves the brainstem, the ventral medial

nuclei of the thalamus, the limbic system, and the frontal cortex. The third circuit

involves the associative areas of the inferior parietal cortex.

Subsequent research has shown that this neuromatrix

also involves other parts of the brain, such as the orbitofrontal cortex, the

prefrontal cortex (Brodmann areas 9, 10, and 44), and the motor cortex (for example,

Brodmann area 6 and the supplementary

motor cortex), as well as certain regions of the midbrain,

such as the periaqueductal

grey matter and the lenticular (or lentiform) nucleus. Many

neuroscientists have even come to regard structures such as the anterior

cingulate cortex and the insula as key areas whose activation necessarily

accompanies certain aspects of pain, and particularly its affective component.

Without reverting to a description of these areas as “pain centres”,

these scientists do note that their neurons show a great deal of specificity to

certain aspects of pain. This shows that the pain neuromatrix may include various

nodes, and that the activity of some of these nodes may be more significant than

that of certain others.

|

|