|

|

In the annals of chronobiology,

the names of two pioneers crop up continually: Colin Pittendrigh,

who discovered the circadian clock in fruit flies and described

the common characteristics of circadian clocks, and Jurgen

Aschoff, who uncovered the physiological mechanisms that

regulate circadian rhythms in birds and mammals, including

humans.

|

Around 1860, French

physiologist Claude Bernard demonstrated a major principle

that governs living organisms, which he named homeostasis. Bernard

defined homeostasis as the organism’s ability to maintain

relative stability in the various components of its internal

environment, despite the constant variations in its external

environment.

Chronobiology has since demonstrated

that homeostasis is very much a dynamic process—by

virtue not only of its responses to variations in external

environmental factors, but also of the body’s many

internal cycles. Some authors, such as neurologist Antonio

Damasio, have even proposed referring to homeodynamic processes

rather than homeostatic ones, to emphasize that there is

not not just one form of homeostasis, but several different

ones, varying with the time of day, the month, and even the

year. |

|

|

The research field now known as chronobiology

deals with the body’s biological rhythms: the way that it

generates its physiological oscillations and keeps its various

systems synchronized.

Ever since the

first findings suggesting that cycles of varying length occur

in the human body, scientists’ understanding of chronobiology

has rapidly grown more complex. They quickly realized that daylight

alternating with darkness was not the source of human circadian

rhythms, but simply the means by which a truly endogenous central

biological clock within the body is kept synchronized with the

hours of day and night. This central clock that is synchronized

by daylight is located in the suprachiasmatic

nuclei of the brain.

Scientists also soon discovered the importance of this cyclicity

in most of the body’s major systems. Whatever physiological

variables researchers measured—such

as cell metabolism, body temperature, or the secretion of various

hormones—each seemed to fluctuate in a cycle with its

own specific peaks and troughs.

Many experiments have been conducted to uncover the subtle connections

among these various rhythms. Some of the greatest insights have

been provided by temporal-isolation experiments,

in which subjects are completely isolated from the usual cues of

alternating day and night, such as daylight and traffic noises.

Numerous researchers have conducted such experiments, to examine

questions such as whether, under such conditions, people continue

to fall asleep at their usual time, or whether their activity cycle

instead begins to run too fast or too slow.

The first temporal-isolation experiments

were conducted in caves, where the temperature is naturally constant

and where subjects can be completely isolated from the outside

world. The first major finding from these experiments was that

the subjects’ circadian rhythms persisted despite this isolation,

which proved that all human beings have an “endogenous clock” inside

their brains.

But these experiments also showed that this

clock was not perfectly accurate: it lost a few minutes every day.

In other words, the subjects’ natural endogenous circadian

cycle was slightly longer than 24 hours, ranging from 24.2 to 25.5,

depending on the study. This may not seem like much, but if someone’s

cycle lasted 24.5 hours instead of exactly 24, then within 3 weeks,

everything that he used to do in the daytime he would end up doing

at night!

These temporal-isolation experiments date

back quite some time. As early as 1938, Nathaniel Kleitman and

his colleague Bruce Richardson spent 32 days in a cave in the U.S.

state of Kentucky, deprived of all time cues. In 1962, the French

researcher Michel Siffre spent two months in an underground glacier

in France’s Maritime Alps. He was 23 years old at the time

of this first experiment, and he spent two more long periods underground

later in his career to measure how the absence of time cues affected

his biological rhythms at various ages. The third time, in 2000,

he was 61 years old and stayed underground with no time cues for

73 days (see box below).

Michel Siffre emerging from his third

time-isolation experiment, in 2000 (AFP)

One of the most spectacular

observations during these time-isolation experiments in caves,

laboratories, and other settings is the way that subjects’ sleep-wake

cycles shift relative to the actual alternation of day and night

in the outside world. But as soon as the experiments are over,

the subjects take only a few days to resynchronize their cycles

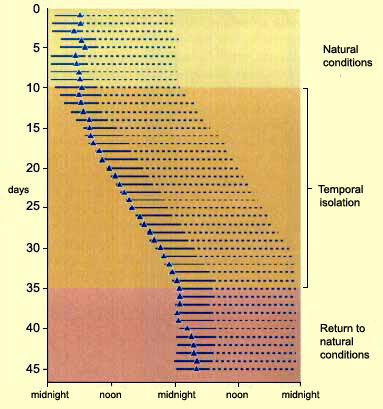

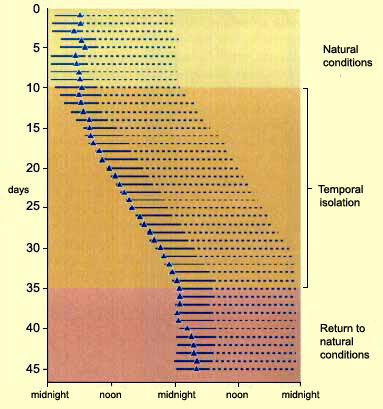

to these external time cues. This shift and the return to normal

are shown in the diagram below, where each line represents one

day in a time-isolation experiment that lasted a month and a half.

The solid part of each line represents the period when the subject

was asleep, the dotted part represents the period when the subject

was awake, and the triangle marks the time when the subject’s

body temperature was lowest.

For

the first 9 days of this experiment, the subject was exposed

to the natural variations in ambient light and noises that

characterize day and night. The first 9 lines of the diagram

thus represent the control records for this experiment. For

the next 25 days, the subject was cut off from all such cues

as to the time of day and was left to operate according to

his own endogenous rhythm. He continued to display a sleep-wake

cycle, but it lengthened to about 25 hours. (After several

weeks of such isolation, these cycles may get even longer—30

to 36 hours. For instance, a subject may stay awake for 20

hours, then sleep for 12, and feel completely fine.) |

(Source: Adapted from Dement,

1976) |

Another interesting phenomenon in these experiments

is that in some cases, the time of lowest daily body temperature

shifts from the end of the sleep period to the start of it. Thus

time isolation may produce shifts not only in behavioural cycles

(such as sleeping and waking) but in physiological cycles (such

as that for body temperature) as well. This desynchronization is

the likely source of the problems

associated with jet lag.

In the last 11 days shown in the diagram,

the subject was placed back in normal alternating conditions of

daylight and darkness. The length of his cycle returned to normal,

and the time that his body temperature was lowest shifted back

toward the end of his periods of sleep.

The first “life

out of time” study that clearly revealed an endogenous

cycle of slightly more than 24 hours in human beings dates

back to 1962. That year, French speleologist Michel Siffre,

already legendary for his previous lengthy underground stays

to experiment with isolation from time cues, spent two months

in the Scarasson underground glacier in southern France.

Siffre used a one-way communication system to tell his research

team back on the surface the times that he woke, ate his

meals, and went to sleep, but he received no information

from them, and he had to estimate the passage of time on

his own. When he emerged from underground, the actual date

was September 17, 1962, but he thought it was only August

20, thus confirming how hard it had been for him to subjectively

recognize how his biological cycle was lengthening.

At that time, nothing was yet known

about the endogenous rhythms of the human body, so Siffre

could not have been influenced by such knowledge in any way.

In this sense, Siffre’s first long stay underground

will always remain one of the “purest” time-isolation

experiments. Soon after, as part of the Cold War, the Russians

and Americans put their own subjects in closed bunkers to

study their ability to live for extended periods in atomic-bomb

shelters.

Michel Siffre conducted two more lengthy time-isolation experiments

with himself as the subject. In 1972, he spent 205 days at

the bottom of Midnight Cave in Del Rio, Texas. Even though

this time, Siffre tended to make automatic corrections based

on his memories of his 1962 experiment, when he emerged from

the cave, his estimate of the date was still two months off!

Siffre conducted his third time-isolation experiment 37 years

after the first. By then, he was 60 years old, and his plan

was to study how his circadian rhythms had altered with age.

He entered the Clamousse cave in southern France on November

30, 1999 and emerged over two months later, on February 14,

2000, thus having entered the new millennium all alone at

the bottom of a cave.

Nowadays, many laboratories are equipped

with rooms that are completely isolated from any fluctuations

in light, sound, and temperature in the outside world. Volunteers

can thus spend several weeks in temporal isolation, or in “forced

desychronization”, a protocol in which they are subjected

to days lasting less than or more than 24 hours. These specially

equipped rooms make it far easier to monitor variations in

the subjects’ physiological parameters during such

experiments.

|

|

|