Tool Module: Your "Mental Stopwatch"

Scientists have

always been intrigued by the human ability to perceive the passage of time. More

specifically, they have wondered whether this ability to feel time passing was

governed by a special “clock” in the brain, or whether it was simply

a by-product of more general faculties such as memory or attention.

One

thing is certain: all humans have a “mental stopwatch” that governs

our perception of time on a scale ranging from a second to a minute. This mental

stopwatch thus occupies the temporal window between the biological clock that

governs our circadian cycles, which have periods of approximately 24 hours, and

all of the oscillations associated with our brain-cell activity, which have periods

measured in milliseconds.

Your mental stopwatch tells you things such as how fast you have to run to catch a baseball, or when to snap your fingers to keep time with a song, or how much longer you can linger in bed once your alarm clock has gone off. This stopwatch also helps you to understand the chronological sequence of events. To understand what someone is saying in a conversation, for example, your brain must recognize the duration of the vowel and consonant sounds you are hearing, mentally organize them into words and sentences, perceive the overall structure of the thoughts they are expressing, and generate a sensible reply at the right time.

Here’s another familiar example. When a traffic light turns yellow as you are driving toward an intersection, you maintain a continuous mental estimate of how long it has been yellow, while comparing this value with your memory of how long yellow lights last. Finally, as you reach the intersection, you decide how much time you have left before the light turns red, and you act accordingly.

As you can readily see, it would be hard to think of any complex human behavioural process in which this mental stopwatch is not involved.

***

The operation of this stopwatch must of course be linked with several other faculties of the brain, such as attention, which lets you note the start and end of time intervals, and memory, which lets you store their duration for future comparisons.

Your subjective perception of time passing is closely connected to how much attention you are paying to the time interval in question. If you find the material that you are reading right now intriguing, then the time you spend reading it will seem short. But if you find it boring, then the time will seem long. You will then take this duration, as you have perceived it subjectively, and transfer it into your working memory. There you can maintain and manipulate your mental representation of this duration for a certain time—for instance, the time it takes to compare with another duration that you have estimated recently, or yet another that you stored in your long-term memory long ago.

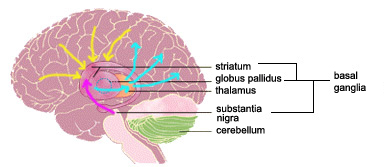

The location of the brain circuits that constitute the physical substrate of this mental stopwatch is still much debated. The basal ganglia and the cerebellum have long been considered prime candidates, because damage to these parts of the brain disrupts behaviours that are necessary for precise calculations of time. But because these abnormal behaviours can also be attributed to more general disturbances of the motor system, the contribution of each of these structures to our ability to perceive durations remains ambiguous.

It has also been hypothesized that the activation of the basal ganglia may occur earlier in this process, for the purpose of encoding time intervals, but that the activation of the cerebellum may occur later, which implies that it is involved in something more than just estimating durations.

Other studies of brain lesions in animals and humans have shown that the frontal and parietal lobes also may be involved in the stopwatch function, but indirectly, through their role in attention and working memory.

Individuals who have suffered right-hemisphere lesions also often have more trouble in estimating durations. This same tendency has been seen in brain-imaging studies in which the right hemisphere has been found to make the greater contribution to duration-comparison tasks.

***

The reason that the mechanism behind the mental-stopwatch function is so hard to understand is that it does not seem to be located in any single area of the brain. Thus it contrasts with our central biological clock, which is located in the suprachiasmatic nuclei, receives definite inputs from the visual system, and triggers circadian behaviours and the cyclical secretion of hormones.

As scientists have acquired more and more data about the anatomy and functioning of the brain, they have proposed various models to try to explain the mechanism by which the mental stopwatch works. The loop circuits connecting the cortex to the basal ganglia thus inspired a model in which the computations of duration were based on the time that a nerve impulse took to make a trip through this loop. In this model, the mental stopwatch was a sort of biological simulator that independently generated a “tick-tock” every time a cycle through this loop was completed.

But this model, which treats duration estimates as something that the brain calculates independently, then adds to our other mental processes, has now been set aside in favour of other models in which the calculation of duration is intrinsically linked to the basic information coming from our sensory inputs. For example, researchers such as Warren H. Meck, of Duke University in North Carolina, have developed a new theory of the mental stopwatch, based on the detection of coinciding oscillations in neural activity.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has played a major role in this research, by letting scientists more accurately observe the brain structures involved in estimating intervals and the chronological sequence in which these structures are activated. Through fMRI, it has been shown that when the brain performs an interval-estimation task, it is the basal ganglia that are activated first, and in particular the striatum, which has a population of richly interconnected neurons that receive signals from many other parts of the brain. The dendrites of these neurons are covered with 10 000 to 30 000 dendritic spines, each of which receives information from a different neuron located in another area of the brain. The striatum is one of the very few places in the brain where there is such a convergence of thousands of neurons on single neurons.

The “coincidence detection” model proposed by Meck and other researchers starts from the fact that the neurons of the cortex have highly varied rhythmic activities. Many of these neurons fire 10 to 40 times per second spontaneously, without receiving any external stimulus. Each of these cortical neurons sends signals to the dendrites of the cells of the striatum, which integrates this special “neuronal music ”. But when a specific event occurs—for instance, when a traffic light changes from green to yellow—the cortical neurons fire simultaneously. This produces a characteristic “evoked potential ”some 300 milliseconds later. This evoked potential acts somewhat like the firing of a starter’s pistol, after which the cortical neurons resume their usual disorderly oscillatory activity.

But because all of these cortical neurons have now been put into phase by the event in question, their resumption of their natural oscillation frequencies causes a typical, reproducible pattern in the striatal neurons onto which they converge. The shape of this pattern varies with the passage of time. According to Meck’s mode, it is this singular pattern of the time that passes after a particular event that the striatal neurons use to measure the elapsed time.

To remember the duration of an interval, such as the amount of time that that traffic light stayed yellow, another brain structure would then come into play: the substantia nigra, which is often associated with the basal ganglia. According to this model, following the event that defined the end of the interval—in our example, when the traffic light changed from yellow to red—the substantia nigra would send out a discharge of the neurotransmitter dopamine. This sudden influx of dopamine would enable the striatal neurons to remember the oscillation pattern that they received at that precise moment, somewhat like a photo that they could subsequently use to identify similar patterns and hence equivalent intervals. For indeed, that is exactly what this model postulates: that every instant after the start of an interval has its own distinct signature.

When a striatal neuron has thus learned the oscillatory signature associated with the duration of a particular event, something different will happen the next time this event occurs: a discharge of dopamine from the substantia nigra at the start, rather than the end, of the cortical neurons’ evoked potential associated with the start of the event. This influx of dopamine would tell the striatal neurons to start analyzing the oscillatory patterns that they were receiving and to continue analyzing them until they recognized the pattern corresponding to the end of the event interval.

At that precise moment, a signal would be sent from the striatum to the thalamus, which communicates with the cortex and the so-called higher functions such as memory and decision-making. Thus the signal would return to the cortex after passing through the striatum, but this time the brain would know how long it has left before the event ends. So, to return to our traffic-light example, you can then decide whether to drive through the intersection or to apply your brakes.

The hypothesized role of dopamine in this mental-stopwatch model is supported by experiments that have been done with individuals who produce less dopamine, such as people with Parkinson’s disease. When these people are asked to estimate the length of time intervals, they invariably underestimate them—in other words, for these people, the time has seemed to pass more quickly. When they are treated with medications that raise the dopamine levels in their brains, their performance improves at least somewhat. People’s dopamine levels also tend to decline as they grow older, starting in their twenties, which may explain why time seems to go faster as you grow older.

The opposite phenomenon also seems to occur: substances such as cocaine increase the availability of dopamine and speed up the mental stopwatch, so that time seems to pass more slowly. Epinephrine and other stress hormones also speed up the mental stopwatch, which may explain why a few seconds can seem interminable when you are having an unpleasant experience.

Lastly, states of intense concentration or intense emotions may overwhelm the mental stopwatch or simply bypass it, thus creating moments where time seems to be suspended or not to exist at all.

As musicians and athletes know, there are ways of training this mental stopwatch to make it more accurate. The average person’s mental stopwatch estimates time intervals with an accuracy ranging anywhere from 5 to 60 % of their actual length, and the margin of error grows with the length of the interval. That is why people still find it so handy to wear an actual watch on their wrist, or to carry a cell phone that displays the time.

Based on: “Times of Our Lives”, by Karen Wright, Scientific American, September 2002

|

|