|

|

| Funding for this site is provided by readers like you. | |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Alzheimer’s-type dementia was not accorded the status of a disease until several decades after it was first described by Dr. Alois Alzheimer in 1906. This attribution occurred gradually, as the relationship between the deterioration of cognitive abilities and the types of brain lesions involved in this form of dementia was discovered. Neurochemical studies of degenerative diseases in the late 1960s and the 1970s had shown especially low levels of certain neurotransmitters in people who had certain disorders: for example, low levels of dopamine in people with Parkinson’s disease and low levels of acetylcholine in people with Alzheimer’s. Pharmacological treatments were then developed to increase the levels of these neurotransmitters, by delivering either precursors of these substances (L-Dopa, in the case of Parkinson’s) or inhibitors of the enzymes that break them down them (cholinesterase inhibitors, in the case of Alzheimer’s). Once medications were available, people naturally drew the inference that they were being used to treat a disease. In this way, the general public began to use the expression “Alzheimer’s disease” to refer to what had long been seen as part of the normal aging process (follow the intermediate Tool Module link to the left). At the same time, researchers were learning more about how aging affects the functioning of the brain. Hence we now better understand the mechanisms responsible for the decline in memory, attention, and language abilities as people age—mechanisms such as inflammation, free radicals, and hormonal changes. And we also now know that factors such as cardiovascular disease, head injuries, and unhealthy lifestyles, as well as genetic and psychological factors, can accelerate these mechanisms that cause the brain to age. Thus we are dealing with a complex situation. We know that in some respects, normal aging of the brain differs from pathological aging, but that in many respects, the two are similar. For example, an older person not known to have any disease will nevertheless have some loss of neurons, albeit minimal and offset by compensatory mechanisms. But in people with Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s, the loss of neurons is massive, irreversible, and specific to certain areas of the brain. Many other issues remain to be clarified, such as the relationship between the presence of amyloid plaques and normal aging (see sidebar), as well as the relationships between the lesions that these plaques produce and the clinical symptoms that are observed. Thus neuroscientists are still debating whether what people call Alzheimer’s disease might not simply be an accelerated form of normal aging. In other words, whether the abnormally high number of lesions in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s represents a specific pathology with its own specific mechanisms, or whether it is simply some kind of speed-up in mechanisms that are already at work in normal aging. Either way, some neuroscientists think that it is time to stop using the expression “Alzheimer’s disease”. For example, Dr. Peter Whitehouse is a neurologist who helped to develop the first medications to treat the symptoms of Alzheimer’s, working with the pharmaceutical industry for over 30 years. He now says that the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease is exclusionary, in both possible senses of the term. First, it is a diagnosis arrived at by default, after all other possible causes of the observed deficits have been excluded. Second, it is a diagnosis that can result in social exclusion for many people. Knowing that you have an incurable degenerative disease can make you feel so stigmatized that you don’t have the heart to maintain your social contacts, even though they might be good for you. Dr. Whitehouse does not deny the existence of sometimes very severe cognitive disorders in older people, but, like more and more of his colleagues, he believes that what people call “Alzheimer’s disease” is not a specific entity. He says that dementias are too heterogeneous to be understood using the current “disease” model, which he considers overly limiting not only for science, but for patients and society as well. For the same reason, he also opposes the concept of “mild cognitive impairment” (see sidebar), which some regard as a specific disorder with symptoms lying somewhere between normal cognition and the deficits associated with other dementias. Indeed, for Whitehouse, the boundaries between Alzheimer’s and other dementias are not clearly defined, and hence Alzheimer’s is not so clearly separated from normal aging as the biomedical model would have us believe. He therefore argues that there is a continuum among various expressions of aging, some of which are more problematic than others. He points out that people are changing constantly throughout their lives and that the ongoing aging of the brain late in life is part and parcel of this continuum. Thus the differences in the ways that the brains of elderly people age can be seen as the result of numerous factors that have influenced them throughout their lives. Some of these factors may be biological, such as cardiovascular problems, insomnia, diabetes, alcoholism, and head injuries. Other may be psychological (such as stress, anxiety, and depression), and still others may be environmental, social, or cultural (such as isolation, financial insecurity, poor nutrition, and limited education). This myriad of interwoven factors makes any clear-cut distinction between “normal” and pathological illusory. Exactly the same interdependency of influences is found in the aging of other parts of the body besides the brain. The condition of elderly people’s joints, for instance, will depend on various genetic factors, as well as environmental factors related to lifestyle. Some people will continue into old age with only minor aches and pains in their joints, while others may have to resign themselves to moderate or even severe loss of physical mobility. And in this latter case, it is not always possible to identify any one pathology that is responsible for the loss. One of the most famous studies that reveals the limitations of our knowledge when it comes to these multifactorial processes is the Nun Study of Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease (see box below). This study showed that one group of nuns whose brains were severely atrophied and contained numerous “senile plaques” may have lived without the deficits associated with Alzheimer’s. And the reverse was also true: other nuns whose brains were almost intact had displayed all the symptoms of Alzheimer’s. Whitehouse therefore believes it urgent for us to reconsider what we are calling “Alzheimer’s disease", so that numerous adults who are still functioning when they receive this diagnosis do not automatically regard themselves as living on a sort of mental death row. As described in the last box below, experiments have shown that an Alzheimer’s diagnosis can itself lead to a decline in a person’s cognitive abilities. According to Whitehouse, the aging of the brain can take a different course if there is sufficient emphasis on lifelong prevention and psychosocial support. As we now know, with dementia, as with many other disorders, regular physical activity, a well balanced diet, and good stress management can delay the onset of symptoms and slow their progress.

Some medications for Alzheimer’s and other dementias are available and can have benefits (though they can also have side effects). But more and more physicians feel that when older people with cognitive losses consult their doctors, medication should not be the only treatment option offered (see second box below). Physicians should also consider all of the psychological and social interventions that may enable these older adults to limit as much as possible the problems caused by the aging of their brains.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Free Radicals and Aging: More Complicated Than We Thought Junk Food and Alzheimer’s: Closer Links Than Once Believed Memory Loss in Alzheimer’s Reduced for the First Time

|

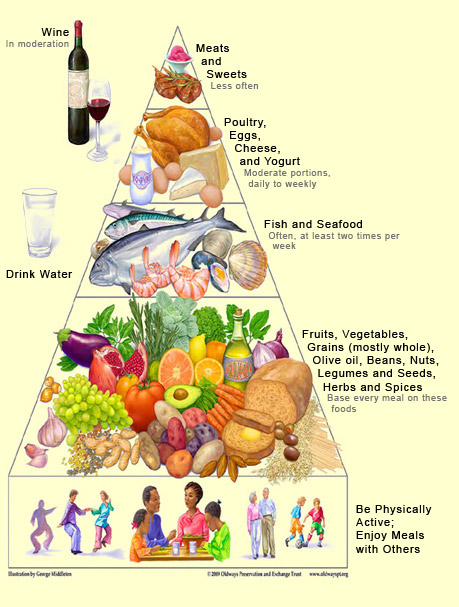

The development of Alzheimer’s-type dementia and the degenerative processes associated with it can be influenced by a great many factors. Whether someone develops the rare, “familial” form of Alzheimer’s is determined entirely by heredity. But whether they develop the more common, sporadic form of Alzheimer’s is determined by the interplay of factors that increase and factors that decrease the risk. Thus, like other chronic conditions, Alzheimer’s can be regarded as a “statistical” disease, the result of the differential between neurotoxic and neuroprotective factors. Obviously, some factors weigh more heavily in the balance than others. For example, age, sex, and the presence of the type 4 allele of the gene for apolipoprotein E (ApoE4) have a more decisive influence than diet or level of education. These first three, most important risk factors are obviously beyond our control—our genetic composition, like our aging, is wholly determined. But might it be possible to reduce the other risk factors through our behaviour—through a healthier lifestyle, for example? In other words, when it comes to environmental risk factors, can we delay the onset of Alzheimer’s, or slow its progress, by adopting neuroprotective behaviours that help to maintain the neuronal reserve and neuronal plasticity in our brains? Over the years, more and more studies have been published about foods, dietary supplements, medications, and simple activities that can reduce certain environmental risk factors for Alzheimer’s. For many of these factors, identified in case-control studies and cohort studies, the preliminary results have aroused a great deal of hope, because they actually seemed to exert a neuroprotective effect. In April 2010, a university-based research centre, with funding from the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH), published a meta-analysis of a large number of these potentially neuroprotective factors. The conclusion of this study was that the data currently available are insufficient to allow the recommendation of any measures whatsoever to prevent Alzheimer’s. In the authors’ view, the encouraging preliminary studies may have been headed in the right direction, but were not conducted with sufficient rigour for public health recommendations to be based on their findings. For example, the authors pointed out, something as basic as the way that Alzheimer’s was defined was inconsistent from one study to another. Hence it would be difficult to recommend specific behaviours that could slow the progress of disorders that were not specific but instead were variously defined. The authors went on to stress the limitations in our knowledge of aging in general (follow the intermediate Tool Module to the left) and of the causes of Alzheimer’s in particular. One of the study’s recommendations was that the scientific community standardize the criteria for assessing cognitive deficits and their progression over time. Another classic problem with studies of this kind is the difficulty in distinguishing causal relationships from mere correlations. It is something like the question of the chicken and the egg: do some people remain mentally alert in their later years because they engage in a lot of physical and social activities, or do they engage in all these activities because they are mentally alert for their age? Many studies show that some such factors are correlated, but not necessarily that one factor is the cause of another. Another issue is that two factors can already be related to each other. For example, people with a higher level of education also tend to engage in more stimulating cognitive activities. While both of these factors seem to protect against Alzheimer’s, it is very hard to tell which of the two is causally related to this protective effect. And of course, it could be both of them, or it could be neither, if there is an as yet unobserved third factor underlying the two others. Though the NIH-funded meta-analysis was very important, we must also avoid the temptation to interpret it as saying things that it does not. For example, it does not say that “there is nothing that can be done to reduce the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease” or that “there is nothing that anyone can do today to improve their cognitive functioning, whether or not they have Alzheimer’s”. All this analysis says is that more rigorous studies are needed before we can make any categorical statements about our ability to influence the progression of Alzheimer’s by changing certain habits in our lives. Moreover, many of these habits are already regarded as excellent for health in several other respects. The first of these habits is a balanced diet, low in saturated fats and high in fruits, vegetables, nuts, grains, fish, and olive oil, along with light to moderate consumption of red wine—in short, a “Mediterranean diet", whose health benefits have long been recognized. These benefits are believed to come from this diet’s high levels of antioxidants that counter the toxic effects of free radicals, as well as from its positive effects on cardiovascular health. According to the NIH-funded study, omega-3 fatty acids, a component of the Mediterranean diet found in fish, among other foods, are one of the factors most often associated with a reduction in cognitive decline.

Next comes physical activity, which is beneficial not only for the cardiovascular system but also for the cognitive functions, according to numerous data that the NIH study still regards as preliminary. But it is hard to see how walking, cycling, or swimming could fail to do some good for people with Alzheimer’s who can still engage in these activities. At worst, even if physical activity were shown to have no favourable effect on the development of Alzheimer’s, it would still be recommended because of its benefits for the rest of the body. The same thing goes for social activity and involvement in one’s community, which in any case break down loneliness and isolation in the final years of life. Even if scientists were to prove some day that social activity does not preserve cognitive faculties, that would in no way diminish the psychological well-being that such activity generates. We have negative evidence of at least one kind of social tie that seems to help maintain cognitive abilities: the NIH study points to a rather robust association between the loss of a spouse and a greater decline in cognitive faculties. It has also been established that participating regularly in stimulating intellectual activities (such as playing cards or chess, doing crossword puzzles, playing music, reading, and writing) throughout one’s life helps to maintain and expand the synaptic area between the neurons. But does keeping one’s mind active by engaging in such activities actually delay the onset of cognitive impairment? The NIH study points to limited evidence that it does, but even this evidence is not consistent. And then there is the Nun Study, famous for its long duration and for the hundreds of elderly nuns who participated in it. One of this study’s findings was that those nuns who had well developed language abilities when they were in their late teens or early 20s were less likely to develop Alzheimer’s late in life. Lastly,

some studies with identical twins (who have exactly the same sets of genes) showed

that about 60% of the total risk of developing the sporadic form of Alzheimer’s

is associated with lifestyle, and only about 40% with heredity. Thus

it seems that it is never too early, or too late, to adopt a healthy lifestyle

that helps to maintain the neuronal reserve and the neuronal plasticity that our

brains need to fight off Alzheimer’s. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|