|

|

In animal studies, researchers

extinguish conditioned fears by ceasing to apply the aversive

stimulus, thus teaching the animals that they no longer have

anything to fear.

Suppose, for example, that researchers

have conditioned a fear in a rat by letting it hear a certain

sound, then applying an electrical shock to its paws through

the floor of its metal cage. The rat soon learns to avoid

the shock by jumping through a door into an adjacent compartment

of the cage where the floor is not electrified. If the researchers

then close the door and start playing the sound without applying

the shock, the rat soon learns that the sound is no longer

associated with the shock and stops trying to get through

the door. The rat's avoidance behaviour is then said to have

been extinguished.

This same process provides the basis for the cognitive-behavioural

therapies that are used to treat anxiety disorders.

|

|

|

| BRAIN ABNORMALITIES

ASSOCIATED WITH ANXIETY DISORDERS |

|

Conditioned fear (follow the Experiment

module link to the left) is regarded as the primary mechanism

underlying many anxiety disorders, such as phobias and post-traumatic

stress disorder. A conditioned fear exists when a neutral stimulus

is strongly associated with an aversive one in a person's mind.

After a while, the neutral stimulus alone suffices to produce

anxiety—for example, when the low rumble of thunder suddenly

plunges a former soldier back into all the horrors of the battlefield.

| Anxiety disorders can be treated successfully

with behavioural therapies (see sidebar) that extinguish the

underlying conditioned fears. This process of extinction involves

gradually weakening the conditioned fear until the conditioned

stimulus (in the preceding example, the sound of thunder) is

no longer associated with the aversive stimulus (the horrors

of battle). In other words, over time, the patient learns how

to overcome the association that he or she had formed between

a neutral stimulus and a fear. In addition to the passage of

time, a change in context can also facilitate the extinction

of a conditioned fear. |

|

|

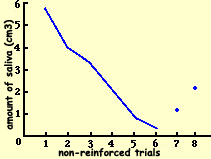

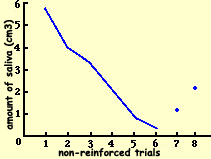

Extinction is thus an adaptive phenomenon:

if the actual threatening situation is not recurring, no purpose

is served by continuing to experience fear simply because its context

has recurred. Researchers have therefore proposed that certain

anxiety disorders may be due to a malfunction in the mechanism

by which conditioned fears are extinguished.

Also, a number of studies have shown that deconditioning through

extinction does not involve actually erasing the conditioning,

but rather learning something new in addition to it. Extinction

is thus different from forgetting.

The original fear is still there; it is simply masked and is no

longer expressed.

|

|

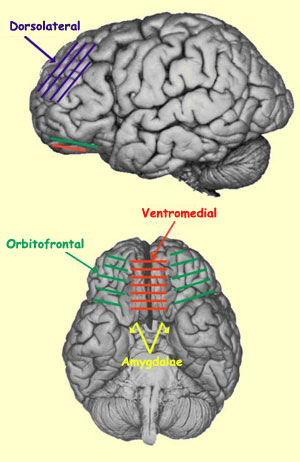

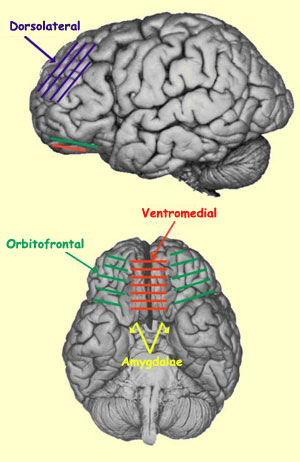

Other experimental data

support the idea that fear conditioning and fear extinction

are carried out by different parts of the brain. The

role of the amygdala in fear conditioning is well established.

The role of the prefrontal cortex in fear extinction is less

well established, but the ventromedial portion of this cortex

definitely plays a role in this process, just

as it does in depression. This makes sense, because the

prefrontal cortex has long been known to play a role in inhibiting

inappropriate behavioural responses.

In experimental studies, when lesions were made in an animal's

ventromedial prefrontal cortex, they did not prevent it from

learning new conditioned fears. But when the researchers then

attempted to extinguish a conditioned fear (for example, by

subjecting the animal to a sound without the accompanying electric

shock that it had previously been taught to expect), the process

of extinction took much longer. |

The precise role of the ventromedial prefrontal

cortex remains ambiguous, however, because it does not seem to

be needed to achieve the extinction itself, but only to recall

the newly learned information some time after extinction has been

achieved. These observations would therefore suggest that this

structure's role is more to consolidate the extinction or to recall

the context in which the extinction took place.

The ventromedial prefrontal

cortex receives connections from the sensory areas and the

amygdala and returns axons to the amygdala. It would therefore

seem well placed to exercise cortical controls over the amygdala—for

example, by

generating the process of extinction. If these cortical

controls are impaired, however, the extinction of a conditioned

fear becomes very difficult. And indeed, one of the most

classic symptoms of damage to the frontal

lobes in human beings is the inability to cease

a behaviour when it becomes inappropriate.

The prefrontal cortex also seems to participate, like the hippocampus,

in the negative feedback loop that lowers the level of stress

hormones when it becomes too high. And like the hippocampus,

the prefrontal cortex might also become impaired by persistently

high levels of glucocorticoids, thus interfering with this

control mechanism and releasing the natural brake on the amygdala.

Consequently, any new emotional stimulus would be more strongly

encoded and would become very resistant to extinction.

|

|

|