|

|

| |

|

| Our Evolutionary Inheritance |  |

| | |

The

Shrinking Human Brain: What Does It Mean?

Why

You Can Have No More Than About 150 Real Friends

The prefrontal cortex seems to contain

an especially large number of long axons, which can make connections

between various regions of the cortex that are far from one another. The larger

the prefrontal cortex, the more long axons it contains, and the more likely consciousness

is to emerge. Brain imaging also shows that the prefrontal cortex is highly active

when tasks of memorization and deductive reasoning are being performed. |

Many researchers, such as anthropologist

Robin Dunbar, say that the main selective pressure that has favoured the growth

of the neocortex in primates has been the growing complexity of their

social groups. According to Dunbar, the dramatic increase in the size

of the prefrontal cortex (compared with the various sensory cortexes, for example)

is explained by the properties of this frontal part of the brain, which have a

great deal to do with social skills.

Though primates are not capable

of elaborate systems of ethics, they do display many moral behaviours, according

to Dunbar. These behaviours of mutual

assistance and co-operation require them to trade short-term costs for long-term

gain, even though this may make them vulnerable to exploitation by more selfish

members of their society. That is why morality may be advantageous from

an evolutionary standpoint. It can strengthen group cohesion and provide a harmonious

social climate that benefits the greatest number of individuals. And what part

of the brain performs the cognitive functions needed to establish such a climate

by restraining selfish tendencies? The prefrontal cortex. |

A study was conducted of men who

had antisocial personality disorder, characterized by irresponsible

actions, cheating, impulsiveness and lack of affect or remorse, and who all had

committed violent crimes. Images of their brains revealed that the neuronal volume

of their prefrontal cortexes was 11 to 14% lower than in normal men.

The prefrontal cortex is recognized as playing an important role in individuals’

moral sensibility and self-restraint. The results of this study provide strong

evidence for this role, and raise some questions about the notion of free will

that is the basis for all law. | |

|

| THE EVOLUTIONARY LAYERS OF THE HUMAN BRAIN |

|

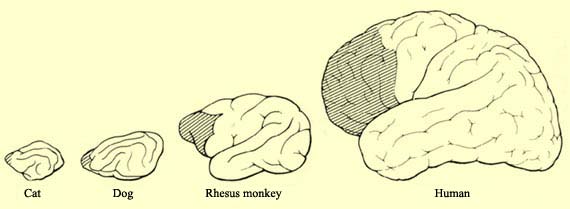

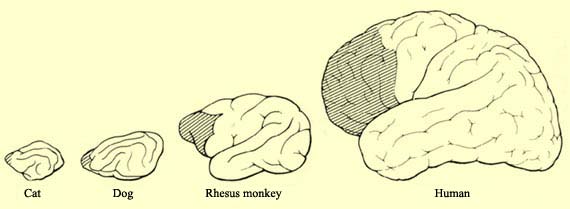

The various species

of vertebrates are very similar in the way that their brains are organized. For

example, all vertebrates have a

forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain, within which are found all the major neural

systems that have evolved to perform functions common to all species.

However, the various species also have areas of the brain that have specialized

in distinctive ways in response to the specific constraints of their environments.

The human brain is about three times larger in volume than we would expect in

a primate of comparable size, and the proportions of its parts to one another

are different than in other primates. For instance, in humans, the olfactory lobe

is only 30% of the size it would be if it were in the same proportion to the entire

brain as in other primates. It follows logically that if the human brain overall

is nevertheless much larger than would be expected in a primate our size, then

some of its other structures must be proportionately far larger. And indeed, when

we trace the brain’s evolution from fish to amphibians to reptiles to mammals

and finally to humans, we see that the

parts of the brain that have grown the most in human beings are in the neocortex,

and more specifically the prefrontal cortex.

The

prefrontal cortex is the most rostral region of the cortex. In other species,

it is dedicated to voluntary motor control, but in primates, it has developed

considerably. For many years, scientists believed that humans’ unequalled

abilities for planning and abstract reasoning were attributable to their having

a more developed prefrontal cortex than other primates. But

studies conducted in the first few years of the new millennium have called this

idea into question. Earlier studies had compared the human brain to those of other

primates, but had not included most of the great apes. In these more recent studies,

magnetic resonance imaging has been used to measure the relative size of the prefrontal

cortex in all species of great apes, including humans. When this new method was

applied to this broader range of species, the relative size of the prefrontal

cortex was found to be almost the same in humans as in the great apes who are

our closest cousins (chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans). According

to the authors of these recent studies, humans’ superior abilities to anticipate

and to plan can more correctly be attributed to other specialized regions of the

cortex and to denser interconnections between the prefrontal cortex and the rest

of the brain. The main reason that the prefrontal cortex is slightly larger relative

to the rest of the brain in humans than in most other primates is that humans

have a larger volume of white

matter in their prefrontal cortex. This white matter is composed of myelin-covered

axons that communicate with other parts of the brain, thus providing greater

connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and the rest of the brain than in other

species.

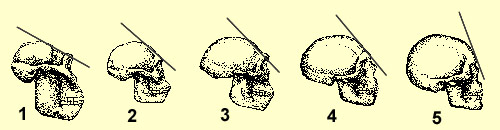

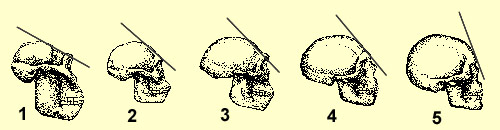

The high, straight forehead

that characterizes modern humans, superceding the prominent brow ridges of others

hominids, is due to the expansion of the cortex, and especially the prefrontal

cortex, in our species.

1.

Australopithecus robustus 2. Homo habilis 3. Homo erectus

4. Homo neanderthalensis 5. Homo sapiens sapiens |

This connectivity is essential for the proper

functioning of our working

memory, in which the prefrontal cortex plays an active role. Working memory

is involved in many of the cognitive abilities that are so highly developed in

humans, such as the abilities to retain information while performing a task, to

verify the relevance of this information to the task in progress, and to keep

the objective of the task in mind at the same time. Patients who suffer severe

injuries to their prefrontal lobes can experience difficulties in relating the

past, present, and future and hence in planning their actions. This phenomenon,

known as “frontal syndrome”, confirms the primary role that this part

of the cortex plays in anticipation and in choices of all sorts.

The

recent expansion of the prefrontal cortex, together with the increased plasticity

and associative capacities of the neocortex, thus seems to be the source of many

of the most typically human cognitive abilities.

Though an increase in

the

size of the brain does not automatically confer any evolutionary advantage on

the species concerned, it has been observed that in the process of hominization,

the hominid species with smaller brains were gradually replaced by species with

larger ones. Some inventive hypotheses have been advanced to explain this

phenomenon. For example, some theorists argue that the greater associative capacities

of individuals with larger brains enabled them to make more unpredictable behavioural

responses. In turn, selective pressure would then have been exerted on other members

of their species to develop larger brains so that they could better predict these

responses — an essential survival skill among social species. These larger

brains would then have generated even more unpredictable behaviours. The positive

feedback loop thus established would have been responsible for this tendency toward

increased brain size in primates. The concept of a positive feedback

loop provides another way of accounting for evolution’s apparent tendency

toward greater complexity. In this case, the selective pressure is seen as being

generated by the evolutionary changes themselves. This pressure is also entirely

dependent on the particular context of the human evolutionary line, with its highly

developed social behaviours. |

Close parallels can be drawn between

the way that the brain has evolved in our species and way that it develops in

an individual. In individuals, just as in species, mutations can arise, and they

can have a significant impact on the adult’s morphology. Even though it

is the adult individual who has been subjected to the selective pressure of the

environment, it is that individual’s genetic development program that will

eventually be selected and passed on to his or her descendants.

Many

researchers think that the expansion of the neocortex in general and the prefrontal

cortex in particular might be explained by mutations in a limited number of genes

at an early stage of development. These mutations would

have resulted in the duplication of certain areas of the cortex, exactly as is

observed for certain genes in the genome. As in the case of genes, one

of the possible advantages of this duplication would be that one particular cortical

region could evolve rapidly while its duplicate continued to perform the basic

function originally assigned to it. |

|

|