|

|

Learning

How To Pique Curiosity

Pleasure is only one part of what we call happiness. Happiness appears to be a far more complex state, one that cannot be reduced solely to the activation of the dopaminergic pathways in the reward circuit. A second necessary condition for feeling happy is the absence of negative emotions, because as soon as we are experiencing fear, anguish, or sadness, pleasure vanishes.

Consequently, anything that reduces the activity of the amygdala, the brain structure associated with negative emotions, brings us closer to the state of happiness. Performing non-emotional mental tasks, for example, reduces the amygdala’s activity, thus providing a biological foundation for the widespread idea that keeping busy is the way to be happy.

But for someone to be happy, yet a third requirement must

be met. The ventral medial prefrontal cortex must be activated,

because it appears to provide the feeling that the world is

coherent and makes sense, which is also necessary for happiness.

Interestingly, in depressive people, the activity of this

region is diminished. |

|

|

| SEEKING PLEASURE AND AVOIDING PAIN |

|

The brain’s main function is to keep the body that houses

it alive and capable of reproducing. Say what you will about human

intelligence, before Mozart’s and Einstein’s brains

could let them produce their works of genius, they had to keep

their owners alive!

Hence it is no surprise that the systems in our brain that influence

our behaviour the most are the ones that let us meet our vital

needs - eating, drinking, reproducing, and protecting ourselves

from danger.

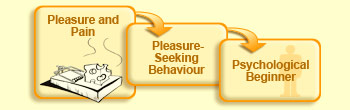

Three phases can be distinguished

in the operation of this powerful organ that maintains the equilibrium

of our body’s internal

environment.

First, in response to stimuli, the brain drives us to

take actions to satisfy our needs. For example, hunger

makes us eat when the glucose in our bloodstream drops below

a certain level. Sexual desire drives us to make love with available

partners. And loneliness makes us go out and meet other people,

to satisfy the more specifically human need to socialize.

|

Second, our actions are rewarded by

sensations of pleasure. But it is important to

note that it is mainly the action itself that is rewarding,

not just the actual reward. For instance, receiving glucose

solution intravenously will get your blood sugar back up

to an appropriate level, but it will never give you as

much pleasure as sharing a good meal with friends. The

action, which often takes the form of a ritual, is therefore

at the very heart of the pleasure experienced.

In the third phase, the feeling of satisfaction

brings an end to the actions–until new signals

trigger new desires. The behaviours that are vital for

our survival are thus under the control of the desire/action/satisfaction

cycle which enables the organism to maintain its integrity.

|

However, such “approach” behaviours

are not always the best way of ensuring your survival. Fight

or flight can also save your life, depending on the situation.

| To feel happy, you not only need to

experience pleasure, you also have to be able to represent

it to yourself. You have to be able to say: “We drank

some wine. It was good. Do you remember? It was for your birthday!" |

|

|