|

|

|

|

|

| Fear,

Anxiety and Anguish |

|

|

|

|

A

neuroscientist gets drunk to explain alcohol’s effects on the

brain

| From the standpoint of evolutionary

survival, anxiety and even anxiety attacks may well have had

some benefits for the human species. Suppose, for example,

that one of our ancestors was walking through a part of the

forest where he had previously been attacked by a wild beast.

He may not have noticed it consciously, but a feeling of anxiety

or anguish triggered by his unconscious emotional

memory may have encouraged him not to linger in this area

again for too long. Similarly, the anxiety that we feel when

we cannot see things at night might encourage us to hide in

the back of a cave until dawn, rather than wander around the

forest where predators might sneak up on us. |

|

|

| WHEN FEAR TAKES

THE CONTROLS |

|

From a psychological perspective, fear,

anxiety, and anguish are three different things. But they are related

and may be regarded as three different degrees of the same state:

the one that people experience when their sympathetic

nervous system impels them to act, but

action is in fact impossible.

Fear is a strong, intense emotion

experienced in the presence of a real, immediate threat. It originates

in a system that detects dangers and produces responses that

will increase the individual’s chances of surviving them.

In other words, it triggers a sequence of defensive behaviours.

In humans, fear can also arise at the mere thought of a potential

danger. The

main neural pathways in which this defensive reaction originates are

well known, as are the

circuits at the centre of this natural alarm system: those

in the amygdala.

Anxiety is a vague, unpleasant

emotion that reflects some apprehension, distress, and diffuse

fears about no one thing in particular. Anxiety can be caused

by various situations. Some examples: having so much information

that you cannot process it all; not

having enough information, so that you feel helpless; having

trouble accepting certain events, such as the death of a loved

one; and experiencing other kinds of unpredictable or uncontrollable

events in your life.

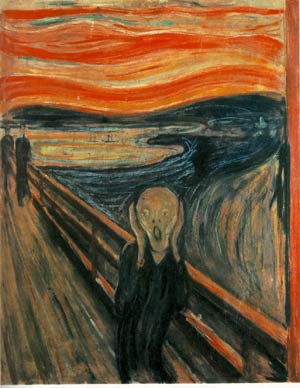

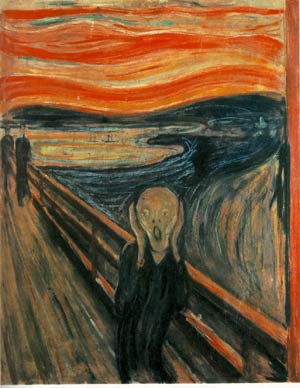

The Scream by Edvard Munch

Anxiety can also result from a specifically

human and hence neocortical process: imagining situations that

do not exist but that you are afraid of. It is this anxiety of

cortical origin that can be relieved by medications such as benzodiazepines,

which potentiate the effect of GABA, the main inhibitory

neurotransmitter in the cortex.

While temporary anxiety is normal and has

no lasting effects, persistent anxiety often inhibits us from taking

action, and this inhibition can

quickly lead to pathological conditions. Chronic anxiety can

also disturb the performance of many cognitive functions such as

attentiveness, memory, and problem-solving.

Though the word “anguish” comes

from the same Indo-European root as “anxiety” (angh,

meaning to tighten or compress), the two conditions differ in that anguish is

always accompanied by physiological changes such as sweating, a

racing pulse, and a feeling of suffocating, while anxiety is not.

Anguish is characterized by the intensity

of the psychic discomfort experienced, which results from extreme

uneasiness, a sense of being defenceless and powerless to deal

with a danger that seems vague but imminent. Anguish often occurs

in the form of attacks that are very hard to control. Victims have

trouble analyzing the source of their anguish, and feeling the

onset of the associated palpitations, sweating, and trembling only

makes them more agitated. People who are experiencing anguish become

focused on the present and can no longer perform more than one

task at a time. They show signs of muscle tension and have difficulty

breathing, as well as digesting their food.

| Fear is a common, natural

emotion. But when it gets out of control, it can lead to many

different mental disorders. For example, generalized anxiety is

a chronic fear with no particular trigger. Phobias are

fears of specific things (such as spiders, crowds, or closed

spaces), taken to the extreme. Obsessive-compulsive disorder often

involves an excessive fear of something, such as germs, that

drives individuals to engage in repetitive rituals to ensure

that they do not come into contact with the thing they fear. Panic

attacks involve the sudden triggering of physical symptoms

of distress, often accompanied by the fear of imminent death. Post-traumatic

stress often occurs when a situation or stimulus reminds

someone of a traumatic experience that they underwent long

ago but that suddenly seems immediately present once again. |

| The stage fright we feel when we have

to address an audience and the stress we feel when we are about

to be put to a test where a lot is at stake are also forms

of anguish, both of which generally dissipate as soon as the

waiting is over and we begin the task at hand. Anguish can

have a positive side, if it lets us mobilize our energies to

give the best of ourselves at key moments. But once again,

it becomes harmful if it paralyzes us and keeps us from taking

action. |

|

|