|

|

|

|

|

| Communicating in Words |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There are two main ways

of classifying languages. Typological classifications

are based on the resemblances between the languages to be

classified, without regard to their origins. According to

this principle, three types of languages can be distinguished.

In inflected languages, such as French,

the words in a sentence change form according to their grammatical

relationship to one another. In agglutinative languages,

such as Japanese, words are formed by the addition of affixes

to a root. In analytic or isolating languages,

such as Chinese, the words tend to be invariable.

In contrast with typological classifications, which do not

address relationships among languages, genetic classifications

attempt to group languages into families all of whose members

derive from a common ancestor. These classifications are established

by historical linguists, who analyze the evolution of languages

through the methods of comparative grammar. These linguists

compare words in different languages for similarities in sound

(phonetics), meaning (semantics), form and grammar (morphology),

and vocabulary (lexicology), then use various criteria to group

the languages into families that have a common origin. This

is the approach used by linguists who believe in monogenism. |

About 6000

languages are spoken in the world today, of which about 1000

are spoken only by very small populations. It is estimated

that nearly half of these 6000 languages are threatened because

they are spoken only by adults who no longer teach them to

their children.

The death of languages is not a new phenomenon. Linguists estimate

that over the past 5000 years, at least 30 000 languages have

been born and died, generally without leaving a trace. But

today, the number of languages spoken in the world is declining

at an unprecedented rate, so that over the coming century,

90% of the languages that exist now will likely disappear.

There would then be only about 600 languages left that would

have proven relatively durable. One of these, of course, will

be English, which is spreading more and more widely and on

its way to becoming the common language of the world.

|

|

|

There are so

many theories about the mechanism by which human language may

have emerged that it's tempting to say that every researcher

who has looked at this question has a theory of his or her own.

But regardless of how language emerged, another question arises

immediately: did it do so once, or many times? In other words,

do all languages have a common origin, a proto-language that

gave rise to all the rest, or did several different dialects

emerge, at various places in the world?

This question opens another great debate

about the origins of language and of the various languages. Those

who argue for the multiple origins, or polygenism,

of language, say that the first modern humans did not share the

potential for the faculty of speech, and that only after they dispersed

through migration did actual languages develop independently among

various groups of Homo sapiens.

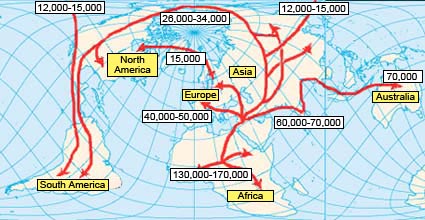

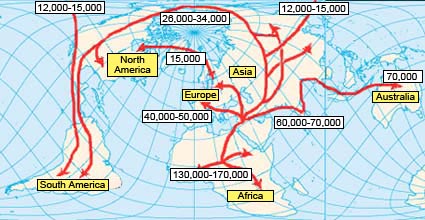

Map of human migrations based on populations’ mitochondrial

DNA

(numbers represent thousands of years before today)

The proponents of polygenism base their arguments

on events and behaviours that would have had little chance of occurring

without spoken language, such as great migrations that would have

required major planning and organizing efforts. From this premise,

the polygenists have deduced, for example, that the peoples who

left Africa and arrived in Australia about 60 000 years ago must

have spoken a complex language before those who migrated to the

Middle East.

The theory opposing polygenism is called monogenism. Its adherents

believe that there was once one proto-language from which all current human languages

subsequently derived. The monogenists include researchers such as the American

linguist Meritt Ruhlen who have attempted to trace the etymological roots of

today’s languages back to their one common ancestor.

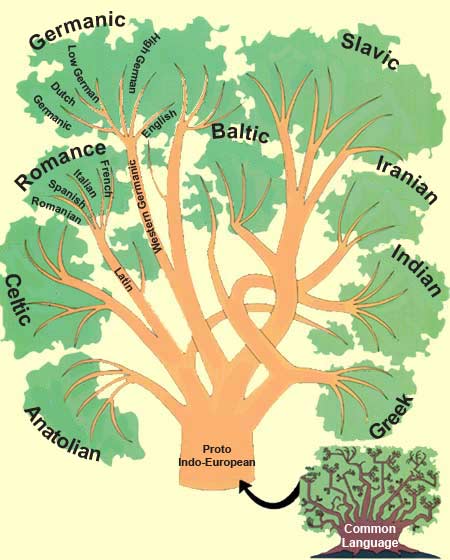

| The record of written languages does

make it possible to use this method to trace the evolution

of today’s languages back a few thousand years with a

fair degree of certainty. In this way, scholars have constructed

an actual family tree that shows how these languages are related

to one another: Latin was the mother of French; Polish is a

sister language of Western Slavic; Scottish and Irish are sister

languages whose common mother is Celtic; the Indian languages

are cousins of the Iranian languages; and so on. |

|

Scholars have now reached a consensus on the existence of about

300 families of languages that date back some 2000 years. Opinions

are more divided about the existence of some 50 “macrofamilies”of

languages dating back approximately 5000 years.

But to go back beyond the beginnings of written

language, which are really quite recent in the overall evolution of language,

scholars must try to reconstruct proto-languages from today’s languages,

which is far more difficult. That is why the thesis that there were 10 or 20 “super-families” of

languages that began to diverge around 10 000 years ago is the subject of so

much controversy.

You can imagine, then, the intellectual battles that broke out after the 1994

publication of Meritt Ruhlen’s On the Origin of Languages, which

posited the existence of a single proto-language over 50 000 years ago! Ruhlen’s

work was based, among other things, on analyses of population genetics that showed

a high correlation between the genetic diversification of human populations and

the diversification of the languages that they spoke.

But other studies have shown the the correspondences between genetic classifications

of populations and genealogical classifications of languages are more uncertain

than was once believed. The fact remains that even though Ruhlen’s work

has been questioned on linguistic grounds, many people still endorse the key

idea in his book: that all languages had a common origin. Among these proponents

of monogenism, there

are two major schools of thought.

The first changes in

the neurons of the left hemisphere that accompanied the development

of language faculties during hominization may have occurred

about 100 000 years ago, or even earlier. But the truly

explosive growth in these faculties most likely began with

the evolution of the angular

gyrus, about 50 000 years ago.

Scientists believe that articulate language as we now know

it must have already appeared 50 000 or 60 000 years ago, because

it was then that the various human ethnic groups became differentiated.

But all these groups still retain the ability to learn any

language spoken anywhere in the world. Thus a Polish or Chinese

immigrant to New York City ends up speaking with a New York

accent, and vice versa, which just goes to show that all of

us have inherited the same linguistic potential.

|

Languages evolve and

change imperceptibly. In Old French, for example, the word “hospital”meant

just what it does in modern English. But in modern French

the “s” has been dropped, and the word is written “hôpital”,

with the circumflex accent over the “o” to mark

where the “s” used to be. Another way that French

has evolved is by adopting English words, such as “cowboy” and “leadership”.

Thus exchanges with other cultures can also influence the

evolution of a language.

A language can evolve significantly in the space of a few centuries.

Just slightly more than 600 years separate today’s English

from the Middle English in which Chaucer wrote Canterbury

Tales, and modern French from a language called Old French

that is now intelligible only to scholars. If you go back still

further in time, you find that French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese,

and Romanian all evolved from Latin. When languages have left

written records, we can thus sometimes trace them back a few

millennia, as in the case of Indo-European, one of the first

known families of languages. |

|

|