|

|

In ancient Greece, active steps were taken to prevent the commemoration of the sufferings experienced by the Ionians. The Athenians, wishing to make people forget the defeat of Miletus by the Persians, forbid any theatrical representations of this subject.

In our own times, the governments of Argentina and Chile have tried to make people forget the atrocities committed by past military regimes so that the very understandable obsession with such memories does not make the exercise of power impossible. That governments today feel compelled to take the same kinds of actions that the Athenian government took some 2,500 years ago says much about the ruling class’s continuing fear of confessing the crimes and mistakes of the past. |

|

|

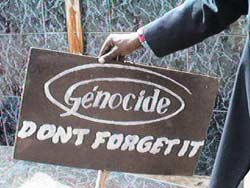

Human communities select the facts and events about themselves that

they will pass on to the next generation. But their collective

memories are riddled with often deliberate gaps regarding the

less illustrious episodes in their history.

One reason for this denial of historic

facts can be a collective sense of shame about such episodes.

The hope may be that if the memory of the atrocities committed

by their ancestors is erased, such events will never recur. But

unfortunately, there are all too many opportunities to repeat

the mistakes of the past. However many times the phrase “never again” has

been repeated, genocide has still not been eliminated.

On the other hand, in countries wracked

by ethnic conflict, such as Rwanda, Bosnia-Herzogovina, and Israel/Palestine,

a social process of forgetting–amnesty, in the literal sense–may be

the only solution. Such a purging of a society’s collective

memory must not obstruct the right to justice and reparation.

But when the process of forgetting

is orchestrated for the benefit of the ruling class, as has

happened many times in history, then we are talking not about

amnesty, but rather about voluntary censorship.

|

|