Tool Module: Apoptosis (Programmed Cell Death)

As

the human nervous system develops, more than half of the neurons that it produces

are quickly eliminated by a programmed process of cell death called apoptosis

(originally a Greek word referring to the falling of leaves in autumn). This elimination

of excess neurons by apoptosis is in fact essential for functional connections

to form between the neurons that remain.

Thus this form of neuronal death

is no disaster, but rather a process that is vital for the organism and that is

triggered by specific signals. This process is often referred to as programmed

cell suicide, because each cell plays an active role in its own disappearance.

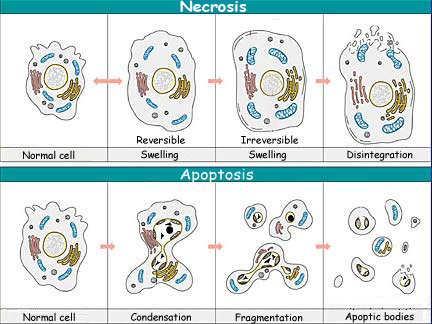

Apoptosis consists of a very precise sequence of events that enables the cell

to be destroyed in just a few hours without leaving any trace.

In this

sense, apoptosis differs from necrosis, which is the other way that a cell can

die and which is far more harmful to the organism. Necrosis is cell death that

occurs accidentally as the result of tissue damage—for example, when the

body suffers a burn or a heavy blow. First the damaged cells swell up, and then

their membranes burst, spilling their contents into the surrounding tissue and

thereby causing inflammation.

The concept of apoptosis was introduced

in 1972 by Kerr and his collaborators to designate a form of cell death that is

totally different from necrosis—one that is far gentler and produces no

inflammation. During apoptosis, a cell undergoes changes that follow a well known

general pattern. First the cell isolates itself from other cells. Then its cytoplasm

and nucleus become very condensed, reducing its volume significantly. Next, its

plasma membrane forms budlike projections that become apoptotic bodies enclosing

part of the cell’s cytoplasm. Lastly, these bodies are phagocytized by the

surrounding cells, which recognize these bodies from a change in the location

of certain molecules in their membranes (phosphatidylserine molecules that switch

from a cytoplasmic orientation to an extracellular orientation).

|

At the biochemical level, during apoptosis, enzymes called caspases

are activated and break down the components that are essential for the cell’s

normal functioning, including structural proteins in its cytoskeleton as well

as proteins in its nucleus, such as enzymes that help to repair its DNA. These

caspases will also activate other enzymes, such as the DNAses that will break

down the DNA in the nucleus.

One of the main characteristics of apoptosis

is that while all these steps are going on, the integrity of the apoptotic cell’s

plasma membrane is never compromised, so that the cell’s contents never

spill out to potentially damage the surrounding cells.

The phenomenon

of apoptosis was first observed by biologists, in the metamorphosis of certain

frogs. The biologists found that the cells in a tadpole’s tail gradually

disappear by apoptosis as it turns into a frog. In the development of vertebrates,

it is through apoptosis that the webs of tissue between the fetus’s digits

disappear, allowing them to become individuated. It is also apoptosis that lets

the endometrium detach from the uterine wall at the start of a woman’s menstrual

period. Lastly, in the immune system, apoptosis is responsible for eliminating

autoreactive T-cells (thus enabling the organism to tolerate itself) and for selecting

the B lymphocytes that will be in charge of the organism’s immune response.