History Module: The Growth of New Neurons in the Adult Human Brain

Scientific knowledge at any given point

in time can be described as the particular set of theories and models to which

the scientific community currently subscribes to explain the world. What makes

science so interesting is that periods of consensus, when a particular scientific

paradigm predominates, are typically followed by periods of radical questioning,

in which the previously received wisdom gets shaken to its foundations.

One example of such a revolution occurred in the neurosciences in the early 1990s.

For over a century, scientists had agreed that in adult mammals, if nerve cells

in the brain were damaged or died, unlike other cells in the body, they were not

replaced. In other words, it was taken as an article of faith that new neurons

never developed in the adult human brain. Each of us was born with as many neurons

in our brains as we would ever have, and for the rest of our lives, the number

of these neurons decreased continuously, though they could continue making new

connections with one another until the day we died.

But for the past

decade or so, this formerly unquestioned assumption has been gradually undermined,

and recent studies indicate that certain parts of the brains of primates, including

humans, may maintain their ability to produce new neurons throughout adult life.

Source:

Barry L. Jacobs, Henriette van Praag, Fred H. Gage

When

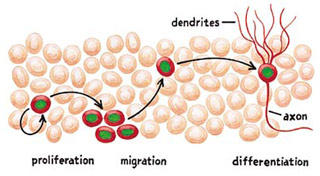

we speak of the “birth” of new neurons,

or neurogenesis, in the adult brain, what we are actually talking about is the

process by which stem cells, such as those found in the hippocampus, divide in

two. One of the two cells will remain a stem cell, while the other will turn into

a neuron.

Through this process, which occurs throughout the body, cells

that could potentially do anything acquire their final specialization: some become

blood cells, while others become muscle or skin cells. And some others, as we

now know, become functional nerve cells, with dendrites and axons that connect

them to other parts of the hippocampus.

The

following paragraphs review the events that led scientists to conclude that functional

new neurons very likely do continue to form in the adult human brain, a process

known as neurogenesis. As we shall see, a scientific revolution such as this one

doesn’t usually happen overnight. More often, a body of observations accumulates

gradually over a long time until it eventually refutes the original concept.

The scientific dogma that no new neurons form in the adult human brain resulted

in part from experiments conducted on rhesus monkeys in the 1960s

(in particular by Pasko Rakic of Yale University). These experiments focused on

the development of synapses to explain the plasticity of the brain.

The

first set of results that began to contradict this dogma were published in 1965.

Working with adult rats, Joseph Altman and Gopal Das of the Massachusetts Institute

of Technology (MIT) reported the birth of new cells in fairly primitive regions

of the brain: the olfactory system and the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. But

these scientists were still uncertain whether these were neurons or glial cells.

In the 1980s, other researchers detected the appearance

of new neurons in the brains of canaries that were learning new songs. Evidence

began to accumulate in other experiments as well, such as an increase in the brain

weight of rats after they had been trained to run labyrinths. But until the 1990s,

most scientists continued to endorse the position that no new neurons ever form

in the adult brain.

In the late 1980s, Elizabeth Gould, who was studying the effects of various hormones on the brain, was puzzled to observe several signs of the birth of new neurons in the rat hippocampus. She mentioned these observations in articles published in 1992 and 1993, but they drew little attention from the scientific community.

In 1996,

Dr. Gould and Bruce McEwen observed that stress reduced the formation of these

new neurons in the brains of rats. These observations drew more attention, because

they appeared to show that the environment could influence the formation of nerve

cells.

In spring 1998, Gould and her team reported having observed neurogenesis in the hippocampus and the olfactory bulbs of adult primates (marmoset monkeys). The following fall, the same observation was made in rhesus monkeys, which are even more closely related to humans. These results in rhesus monkeys were soon confirmed, in May 1999, by David R. Kornack and Pasko Rakic.

In November 1998, the team of Swedish researcher Peter Eriksson and American researcher Fred H. Gage published a study demonstrating that new neurons are generated in the dentate gyrus of the adult human brain. The study also showed that these new neurons were produced from stem cells, then migrated through the granular layer and differentiated into mature neurons with axons and dendrites.

In March 1999, Gould’s team further refined its observations by showing that the extent of neurogenesis was proportional to the amount of cognitive stimulus that the animal received from its environment. Thus, an enriched environment would promote neurogenesis while an impoverished environment would reduce it. Likewise, rats that interacted socially were found to have more new neurons than rats that were isolated in individual cages.

In October 1999, Dr. Gould published an article, in the journal Science, stating that new neurons were produced in three associative regions of the neocortex of adult rhesus monkeys: the prefrontal, inferior temporal, and posterior parietal cortexes. These regions are involved in higher cognitive functions such as decisionmaking, short-term memory, recognition of faces and the position of objects in space, and so on. Many scientists found it far harder hard to accept the idea that even this most recently evolved part of the brain could generate new neurons.

In 2000, Eriksson and Gage published another study, in which they showed that new neurons are generated in the dentate gyrus of people up to 72 years of age.

Also in 2000, other articles appeared that linked neurogenesis in the hippocampus with depression. Researchers already knew that stress slowed down neurogenesis. Now they observed that therapeutic interventions that increased the level of serotonin in the brain also increased neurogenesis. The idea that neurogenesis might play a role in precipitating and curing episodes of depression began to be discussed more and more.

In December 2001, Rakic published an article in which he contradicted Gould’s results and concluded that though neurogenesis does in fact occur in the hippocampus of adult primates, there is no compelling evidence that it does so in their neocortex. The debate on this issue continues.

In February 2002, Henriette van Praag, Fred H. Gage, and their team reported that the membranes of the new neurons generated in the hippocampus of adult mice have normal properties that enable them to propagate action potentials and form functional synapses. The finding that new neurons can develop in various parts of the brain and establish functional connections with the neurons that were already there opens new prospects for the treatment of degenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

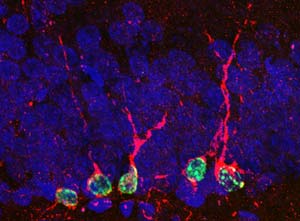

Source: Heather A. Cameron

One-week-old neurons newly developed in the dentate gyrus of an adult rat brain

The

story continues…

This story of how researchers determined

that new neurons do form in the brains of adult primates shows how most scientific

“discoveries” are made. The process

involves not so much the sudden revelation of a clear-cut fact as the long, gradual

accumulation of observations that contradict the initial state of knowledge. These

“anomalous” observations generate

new hypotheses (for example, that neurogenesis may occur in some other, more highly

evolved species, or in some other part of the brain), which lead to new experiments.

After a time, scientists put the newly observed facts together and formulate

a new theory. In the case described above, the new theory was that, contrary to

what was then believed, in certain regions of the primate brain, neurogenesis

does not stop when the animal reaches adulthood, but instead continues throughout

its life.

Thus stated, this theory has enough supporting evidence that

it is now widely accepted by the scientific community. As mentioned above, however,

the same cannot be said for the question of neurogenesis in the neocortex of primates.

In this regard, the data are still too contradictory to extend the new theory

to this part of the brain. Further experiments will be needed to tip the balance

in one direction or the other.

The moral of this story is that when you

see sensational headlines trumpeting some scientific finding as a sudden lucky

discovery or the product of one scientific genius who has taken the world by storm,

you should always be skeptical. As the above chronology indicates, Elizabeth Gould’s

research, for example, was only the latest in a long series of experiments dating

back to the 1960s, or even back to early 20th century, when Ramon y Cajal conducted

the first experiments in staining neurons. From an even broader perspective, her

research is part of all the scientific efforts that have enabled us to begin to

get a better understanding of the functioning of the human brain.