|

|

|

|

|

| Making

a Voluntary Movement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 1939, to solve certain

problems caused by repetitive manual labour on assembly lines

(but with the ultimate goal of increasing productivity even

further), Harvard University began conducting a research

project for Western Electric.

Somewhat randomly, the Harvard researchers began to modify

certain factors in the organization of work, such as lighting,

the timing and duration of workers' breaks, and overall work

schedules. Curiously, no matter what changes were made, productivity

increased. The conclusion: when managers take an interest in

workers (or pretend to do so), they produce more because they

feel valued.

In another classic experiment, when workers in a plant were

divided into two groups, and one was given a vitamin and the

other a placebo, absenteeism decreased by the same amount in

both groups. This discovery (named the Hawthorne effect,

after the name of the Western Electric plant near Chicago where

the experiment was conducted) gave rise to the human-relations

trend in corporate management.

|

|

|

| THE ORGANIZATION

OF MANUAL WORK |

|

Taylorism became

the dominant method of organizing work in the early 20th century.

Based on separating the design of tasks from their performance,

it allowed for tremendous gains in productivity compared with

pre-industrial, artisanal production.

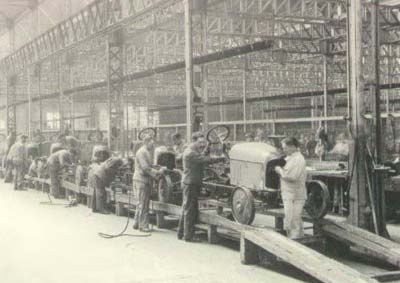

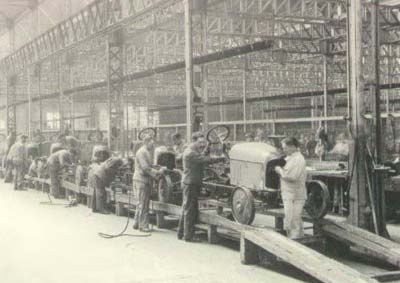

As early as 1908, automobile manufacturer Henry Ford saw the many

benefits that his industry could derive from applying Taylor's

theories. When Ford introduced the assembly line to build his Model

Ts, Taylorism became Fordism. The term Fordism thus refers to the

rationalization of the Taylorist method of organizing work through

the creation of assembly lines, which made standardization and

mass production possible.

|

The advantage of the assembly line was that it brought the

work to the worker instead of making the worker go to the

work. In Ford's auto plants, workers were never supposed

to have to stoop, stretch, or take more then one step in

any direction. By the 1920s, thanks to the assembly line,

it took only 1/12 as much time to build an automobile as

it previously had. |

By continuing to promote the division of

tasks, the ideologues of Fordism soon revealed the limitations

of these principles. By reducing workers to the status of machines,

these principles ultimately impaired the profitability of the enterprise

itself. With the depression of the 1930s, social protest movements

also emerged to which employers were forced to respond.

As a result, bosses began to pay special attention to "human

relations" within the firm. To put it more clearly, they tried

to get workers to identify subjectively with the company's goals.

Improvements in the work environment in terms of atmosphere, physical

amenities, and communication also had positive impacts on employees'

productivity (see sidebar).

During this same period, some unionized workers began to stress

the importance of enriching jobs by giving workers tasks from which

they could derive a sense of personal achievement. It was also

during this period that ideas such as decentralization and self-management

were first raised.

Since the 1950s, technological progress has brought significant

changes to the principles of Taylorism and Fordism. The old-fashioned

assembly line was divided into a series of fixed workstations constrained

by the slowest operation. But now, instead of being treated as

an additive process, production is regarded as a continuous flow.

Production workers' jobs have come to include a larger element

of monitoring and supervision, in which semi-autonomous teams organize

themselves, assign their own tasks, and make their own decisions

concerning production.

These employees are also expected to control the quality

of their own product and maintain their own machines. If

problems arise, the team members co-operate to get production

going again. And if the company makes changes in its product

line or processes, these workers must be able to adapt to

them. This versatility lets the company reduce downtime and

increase productivity. In short, this form of job enrichment

makes employees feel that they are "indispensable". |

Source: Denis Simard, Cégep

Sept-Iles

Source: Denis Simard, Cégep

Sept-Iles |

This production method is often called Toyotism,

after the Japanese automobile maker Toyota, which was the first

to put it into practice. In this method, productivity gains no

longer come from simplifying tasks and intensifying the work pace,

as in Fordism, but instead come from increasing workers' flexibility

and thus maximizing their usefulness to the company. In both cases,

however, the company's objective is still to increase productivity

and thus increase its profits by getting more out of its workers.

The robots used

on assembly lines are machines designed to replace human

hands. These machines can be programmed to perform myriad

tasks with strength and accuracy, in locations that would

be dangerous, hostile, or hard to access for human beings.

While automated machines repeat the same operations indefinitely,

robots can make certain choices. This flexibility in their

operating cycle is made possible by the computers that control

them. Some robots are shaped like human beings and are therefore

called androids.

|

|

|